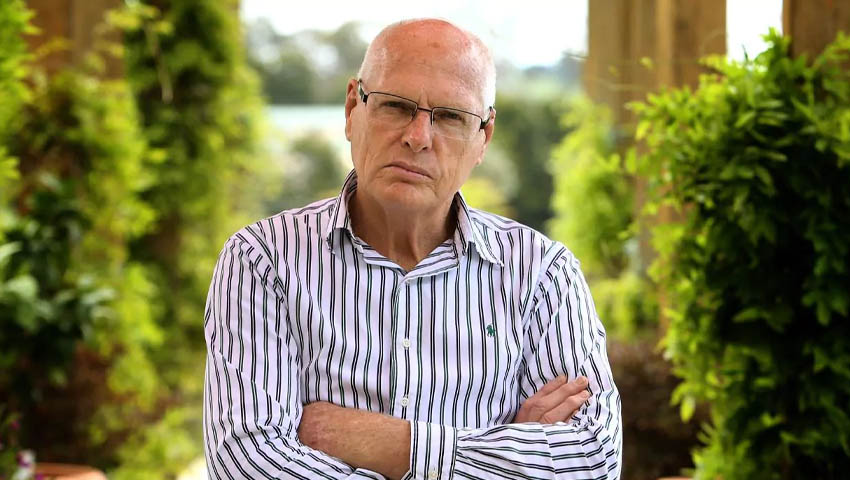

Former Australian Major General turned senator Jim Molan has long been an advocate of an all encompassing National Security Strategy to bring together the individual components of Australia’s national security apparatus – with the regional and global balance of power changes serving as powerful catalysts to prompt such a policy development.

To continue reading the rest of this article, please log in.

Create free account to get unlimited news articles and more!

National security has traditionally focused on ‘hard power’ concepts of conventional economic and military power, espionage and intelligence gathering – however, in an increasingly challenging global environment, does a true national security strategy require a more holistic response?

National security in the contemporary context is best defined by US academic Charles Maier: "National security ... is best described as a capacity to control those domestic and foreign conditions that the public opinion of a given community believes necessary to enjoy its own self-determination or autonomy, prosperity and wellbeing."

Recognising the traditional 'hard power' elements of national security policy and strategy, which is the key responsibility of any government – namely elements of political, economic and military power – Australia has long enjoyed a period of relative stability and consistency that has empowered the nation, but also engendered a sense of complacency.

Australia has long had a tough relationship with the ‘tyranny of distance’. On one hand, the nation’s populace has treated it with disdain and hostility, while Australia’s political and strategic leaders have recognised the importance of geographic isolation.

The rise of Indo-Pacific Asia means the ‘tyranny of distance’ has been replaced by a ‘predicament of proximity’. China, India, Indonesia, Thailand, Japan and several other regional nations are reshaping the economic and strategic paradigms with an unprecedented period of economic, political and arms build-up, competing interests and rising animosity towards the post-World War II order Australia is a pivotal part of in the region.

This rapidly evolving global environment, combined with the increasing instability of the US administration and its apparent apprehension to intervene or at least maintain the global rules-based order following the radical shift in US politics, also forces Australia to reassess the strategic calculus – embracing a radically new approach to national security strategy and policy.

Defence Connect recently spoke with former Army Major General (Ret'd) and senator for NSW Jim Molan to discuss the importance of developing and implementing a holistic national security strategy

We're half way there – Individual strategies and plans mean nothing without an over arching strategy

Australia has recently undergone a period of modernisation and expansion within its national security apparatus, from new white papers in Defence and Foreign Affairs through to well articulated and resourced defence industrial capability plans, export strategies and the like in an attempt to position Australia well within the rapidly evolving geo-strategic and political order of the Indo-Pacific.

Each of the strategies in and of themselves serve critical and essential roles within the broader national security debate. Senator Molan stressed the importance of these developments, telling Defence Connect, "We have managed to get away with not having a national security strategy only because we have lived in a tranquil region since 1945. But our strategic environment is changing quickly, and we need to prepare for a turbulent future. Developing a national security strategy would be a vital first step towards building the capacity we need to face the potential challenges that are coming."

"Most Australians can be forgiven for believing that successive Defence white papers, in conjunction with Foreign Affairs white papers and reviews into energy, including liquid fuels, water and food security, constitute a true national security strategy, unfortunately, without the guidance of an overarching national security strategy, we get lost in the sub-strategies."

Australia's conundrum – Responding to the very real limitations of US power

One of the core challenges facing the US in the Indo-Pacific and, more broadly, key allies like Australia, Japan and South Korea, is the growing atrophy of America’s armed forces in the region, and the report cites a number of contributing factors directly impacting the capacity of the US to wage war, particularly as China, a peer competitor, presents an increasingly capable, equipped and well-funded array of platforms, doctrine and capabilities.

Indeed, the limitations of US power has recently been recognised and articulated by the US Strategic Studies Centre (USSC), which stated: "America has an atrophying force that is not sufficiently ready, equipped or postured for great power competition in the Indo-Pacific – a challenge it is working hard to address. Twenty years of near-continuous combat and budget instability has eroded the readiness of key elements in the US Air Force, Navy, Army and Marine Corps. Military accidents have risen, ageing equipment is being used beyond its lifespan and training has been cut.”

In doing so, the USSC recognises that for the first time, America has a true competitor in China – a nation with immense industrial potential, growing wealth and prosperity, a driving national purpose and a growing series of alliances with re-emerging, resource rich great powers in Russia, and supported by a growing network of economic hubs and indebted psuedo-colonies throughout the Indo-Pacific and Asia.

Whether consciously recognising the potential of this challenge or not, the US President’s direct, often confrontational approach towards allies belies domestic concerns about America’s ability to maintain the post-Second World War global order. Andrew Davies of ASPI highlighted the importance of recognising the limitation of US power in a recent piece for ASPI, saying, "The assumption of continued US primacy that permeated DWP 2016 looked heroic at the time. It seems almost foolishly misplaced now."

Senator Molan expanded on this, explaining to Defence Connect, "Australia has had one previous attempt at putting a national security strategy in place under the Gillard government in 2013. Although it was a decent first attempt, it is has already been overtaken by events. Terrorism was the principal security challenge it focused on, and although the threat of terrorism has not disappeared, other changes in the world are demanding our focus.

"The world has changed dramatically in the six years since the release of the last national security strategy. Of primary concern is the decline of American power. At the end of the Cold War, the US planned for the contingency of fighting, and winning, ‘two and a half wars’ simultaneously. This meant it could wage two large scale regional wars and a small scale conflict elsewhere and prevail in all of them."

Australia emerged from the Second World War as a middle power, essential to maintaining the post-war economic, political and strategic power paradigm established and led by the US – this relationship, established as a result of the direct threat to Australia, replaced Australia’s strategic relationship of dependence on the British Empire and continues to serve as the basis of the nation’s strategic policy direction and planning.

The nation is uniquely located, straddling both the Indian and Pacific Ocean at the very edge of south-east Asia, enhancing the nation’s status as the key regional ally for the US – with Australia increasingly dependent upon the economic stability and growth of major established and emerging economic, political and strategic Indo-Pacific powers, namely China, Japan, India, Korea and smaller nations.

Recognising this, Australia’s security and prosperity are directly influenced by the stability and prosperity of the Indo-Pacific, meaning Australia must be directly engaged as both a benefactor and leader in all matters related to strategic, economic and political security, serving as either a replacement or complementary force to the role played by the US – should the US commitment or capacity be limited.

Regardless of the question, a National Security Strategy is the answer

By its very nature, national security strategy and policy is an all encompassing area of public policy – indeed every facet of contemporary public policy is crucial to supporting the broader national security debate. From seemingly banal aspects of social security and health policy, through to infrastructure development, water security and agriculture policy, each element of public policy is intimately enmeshed as part of the broader national security conversation.

Recognising this critical factor – how does Australia respond to the rapidly evolving regional environment and develop a holistic national security strategy?

For Senator Molan, the answer is undoubtedly a unified, over arching National Security Strategy, "A national security strategy must start with the challenges Australia faces in its strategic environment, it can't start anywhere else. If you don't know what you're going to fight, how you're going to fight it and when you're likely to fight it and how you can win it, because winning is everything, then you can't do a national security strategy.

"Only the government can properly combine all the input from Defence, Foreign Affairs, Australia's intelligence community to formally design and implement a national security strategy, to guide all the key public policy elements to form such a policy."

Your thoughts

Australia's position and responsibilities in the Indo-Pacific region will depend on the nation's ability to sustain itself economically, strategically and politically. Despite the nation's virtually unrivalled wealth of natural resources, agricultural and industrial potential, there is a lack of a cohesive national security strategy integrating the development of individual, yet complementary public policy strategies to support a more robust Australian role in the region.

Contemporary Australia has been far removed from the harsh realities of conflict, with many generations never enduring the reality of rationing for food, energy, medical supplies or luxury goods, and even fewer within modern Australia understanding the socio-political and economic impact such rationing would have on the now world-leading Australian standard of living.

Enhancing Australia’s capacity to act as an independent power, incorporating great power-style strategic economic, diplomatic and military capability serves as a powerful symbol of Australia’s sovereignty and evolving responsibilities in supporting and enhancing the security and prosperity of Indo-Pacific Asia. Shifting the public discussion away from the default Australian position of "it is all a little too difficult, so let’s not bother" will provide unprecedented economic, diplomatic, political and strategic opportunities for the nation.

However, as events continue to unfold throughout the region and China continues to throw its economic, political and strategic weight around, can Australia afford to remain a secondary power or does it need to embrace a larger, more independent role in an era of increasing great power competition?

Let us know your thoughts and ideas about the development of a holistic national security strategy in the comments section below, or get in touch with

Login

Login