Has the Chinese military’s recent projection of power in the region unmasked the Xi regime’s true ambitions?

To continue reading the rest of this article, please log in.

Create free account to get unlimited news articles and more!

Over the weekend, Defence reported an incident in which a People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) Shenyang J-16 strike fighter intercepted a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) P-8 Poseidon conducting “routine maritime surveillance activity” in international airspace over the South China Sea.

During the incident, which took place on 26 May, the fighter jet cut across the nose of the Australian surveillance platform, releasing a “bundle of chaff” ingested into the RAAF aircraft’s engine.

The “very dangerous” manoeuvre was condemned by Defence Minister Richard Marles, who said it would not deter the RAAF from conducting future missions over disputed territory.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese later revealed the government had made “appropriate representations” to the Chinese government expressing concern over the incident.

On the same day, a Chinese aircraft confronted a Canadian military aircraft enforcing United Nations sanctions along the border with North Korea, failing to adhere to international air safety norms.

These incidents came just days after Chinese and Russian bombers flew over the Sea of Japan and East China Sea during the Quad leaders’ meeting in Tokyo.

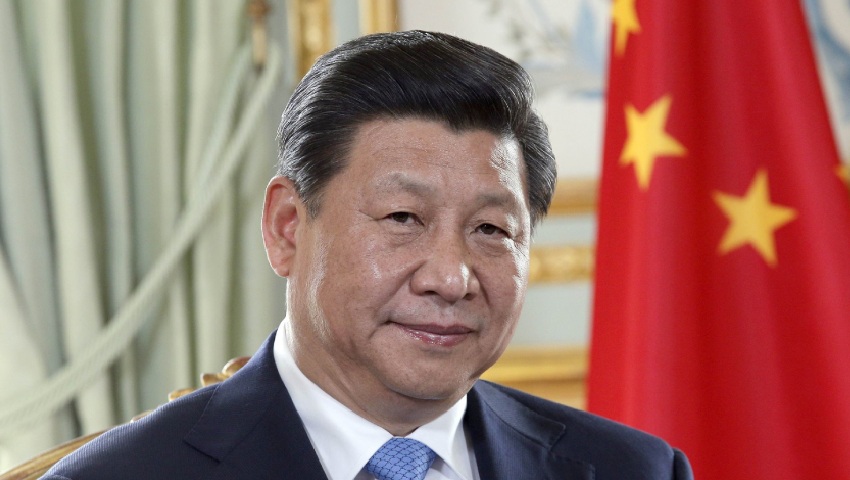

So, what do these aggressive manoeuvres tell us about Chinese President Xi Jinping’s ambitions in the region?

According to Michael Shoebridge, director of ASPI’s defence, strategy and national security program, these incidents suggest Xi wants to present the PLA as a “risky, dangerous entity to approach”.

“The Chinese military is acting under Xi Jinping’s instructions to be ‘primed to fight at any second’,” he writes.

“The PLA is comfortable using force during peacetime, and even has a term for this: ‘peacetime confrontational military operations’.

“So, the Canadian and Australian examples are not local Chinese commanders or even individual pilots acting on their own. They are doing what Xi and the PLA high command want and expect.”

Shoebridge claims these actions dispel any hopes of a balanced “reset” of diplomatic relations between Canberra and Beijing.

“Of course, if Beijing was at all serious about any positive ‘resetting’ of its relationship with Australia, it could have instructed its military to refrain from such hostility. But it hasn’t,” he continues.

“Its rhetoric of resetting is all about seeking policy change in Canberra and allowing Beijing to dictate both what it wants from Australia and what we have to do to achieve that.

“Beijing could also apologise to Australia and Canada and discipline the PLA pilots involved and their commanders.”

Shoebridge argues Xi has no intentions of cooling tensions, but rather stoking “violent nationalism”, turning diplomas into “wolf warriors”.

In authorising these acts of military aggression, Xi wants the international community to believe it must “live with how the Chinese leadership chooses to use its military power”.

“It’s trying to normalise its behaviour and force others to adjust in response,” he adds.

“Sophistication and nuance are not something Xi and his officials and military are practising.

“Instead, hard power, assertion, coercion, aggression and denial are the primary characteristics of Xi’s ‘new era’.”

The joint bomber flights, he adds, prove Russia is China’s “no limits partner in aggression”.

To counter this, no individual nation impacted by Chinese aggression should isolate itself through bilateral discussions.

“The broad, united approach to facing down Putin in his horrific war must be applied to the China-Russia strategic partnership,” he adds.

Shoebridge goes on to draw a connection between the recent spate of PLA aggression and Beijing’s push in the South Pacific.

China’s Foreign Minister, Wang Yi, had proposed the “China-Pacific Island Countries Common Development Vision”, which offers intermediate and high-level police training for Samoa, Tonga, Fiji, Kiribati, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, the Cook Islands, Niue, Vanuatu, and the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM).

This was accompanied by a five-year action plan, which calls for ministerial dialogue on law enforcement capacity and police cooperation.

This included the provision of forensic laboratories, cooperation on data networks, cyber security, and smart customs systems.

The plan also advocated for a “balanced approach” on technological progress, economic development and national security – backing a China-Pacific Islands Free Trade Area and joint action on climate change and health.

However, Beijing has reportedly withdrawn its proposal after it was met with resistance from some Pacific Islands leaders.

President of the FSM David Panuelo condemned the deal, with Reuters reporting other nations, including Niue, requested an amendment or a delay to the decision.

“How glad the 10 nations who didn’t sign Beijing’s proposed regional security pact must be that they rejected this offer,” Shoebridge writes.

“The Canadian and Australian incidents, together with the joint Russian-Chinese bomber mission are graphic demonstrations of why enabling the Chinese military to operate more routinely and easily in the South Pacific—as Beijing wants and as Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare is helping happen—is bad news for South Pacific nations.”

He concludes: “This is ‘security assistance’ the PLA way.”

Get involved with the discussion and let us know your thoughts on Australia’s future role and position in the Indo-Pacific region and what you would like to see from Australia's political leaders in terms of partisan and bipartisan agenda setting in the comments section below, or get in touch with

Login

Login