Not since the years preceding the Second World War has Australia’s geo-strategic reality been more unpredictable – the rise of China, combined with the relative decline of the US, the emergence of other regional powers and asymmetric threats all challenge long-term national security, explains Dr Ross Babbage.

The challenge of providing effective security for Australia has been demanding in the past, but now it is truly daunting. We need to revisit some of our defence and broader national security thinking, develop a more cohesive game plan and make sure that we don’t waste any of the limited resources that we can commit to the task.

A fundamental problem is that Australia suffers from a mismatch between its geographic scale and its defence resources. The Australian continent is a similar size to the continental US, Australia also has several offshore territories that are as far from the mainland as Hawaii is from North America.

But Australia’s population, economy and tax base are comparable to those of Texas. Australia needs to secure itself with a defence budget that is less than one-fortieth of that which is available to the Pentagon.

This funds a permanent defence force that numbers just over half a Melbourne Cricket Ground crowd. Hence, a central challenge for Australian defence planners is how to strengthen deterrence and defensive capabilities in the more demanding strategic environment now developing when the country’s independent resources are so limited.

A further serious complication is that Australia now finds itself close to the centre-stage of superpower rivalry and a likely region for any future major war. Australia is no longer a strategic backwater and its strategy and security planning need to be restructured appropriately.

Australia is also now of greatly increased geo-strategic importance to both the US and also to a number of rapidly rising powers. While some Australians might prefer to distance themselves from heightened major power competition, such tensions are taking an increasing and unavoidable interest in us.

Several important consequences flow for Australian defence planning.

First, Australia may be confronted in the future by a serious conflict initiated by major powers that is focused in Australia’s region. Moreover, the nature and form of such a war would probably be markedly different from the more limited contingencies that have driven Australian defence planning for the last 50 years.

Second, there is no sound basis for assuming that Australia will receive an extended period of clear warning prior to a major conflict in the Indo-Pacific. Australian defence planning needs to assume that unless capabilities can be operational within a month they may have little relevance for the initial phases of such a conflict.

Third, were a major war to erupt between the major powers in the Indo-Pacific, its duration may not be short. Indeed, senior allied defence analysts have concluded that it could extend for many months or even years.

Largely as a result of the above factors, Australia’s close ally, the US, now has a much stronger interest in operating on and from Australia in close partnership with the ADF.

Many regional countries share Australia’s concerns about the changing strategic situation. If the government takes up the resulting opportunities to develop closer security partnerships across the Indo-Pacific, Australia may have more opportunities to shape a favourable strategic environment than at any other time in its history.

In order to respond effectively to our markedly different strategic circumstances, six key steps need to be taken.

First, the Australian government must explain more effectively to the community the changing nature of the country’s security challenges and the need to take new defensive measures.

Second, the government needs to re-state the country’s core security objectives and define a new grand strategy that is tailored for the more challenging times ahead. I have argued in detail elsewhere that a strategy of partnership and leverage would be effective in the new era.

Third, the government needs to re-state its commitment to spend a minimum of 2 per cent of GDP on defence so as to strengthen Australia’s independent capabilities to defend the country’s most vital security interests.

Fourth, in order to greatly strengthen Australia’s deterrence, and also the credibility of the US extended deterrence commitment, Australia should offer to host a wide range of American combat and combat support units in Australia on a permanent basis. This would greatly ease American basing pressures, reduce the prospect of conflict escalation and take the Australian-American alliance to a new level. Australia should strive to become the indispensable American ally in the Indo-Pacific.

Fifth, Australia needs to refocus and re-energise its programs to strengthen strategic partnerships with a range of priority regional countries, especially Japan, China, South Korea, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea and the island states of the south-west Pacific.

Sixth, Australia needs to strengthen its domestic resilience to prepare for potential energy, food, biological, chemical and cyber security challenges in the years ahead. We also need to take serious measures to protect our critical defence capabilities such as our air and naval bases as well as key components of our civil infrastructure so that these key nodes cannot be destroyed in the first days of a war.

In short, it is time for Australians to become much better informed about the markedly different strategic landscape that is developing. Australians need to look beyond their domestic preoccupations and debate the best ways of strengthening the country’s security for the more demanding times ahead.

It’s time for Australians to lift their game.

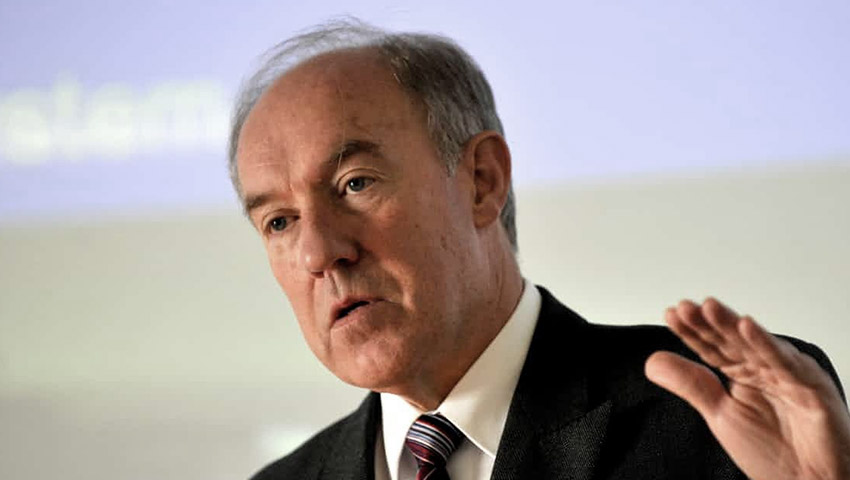

Dr Ross Babbage is CEO of Strategic Forum in Canberra and a non-resident senior fellow with the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA) in Washington, DC. He has formerly held senior positions in the Department of Defence, the Office of National Assessments, the corporate sector and at ANU.

This article summarises some of the conclusions of: Game Plan: The Case for a New Australian Grand Strategy, which has been published by the Menzies Research Centre and Connor Court.