China has moved to expand its soft power into Australia’s backyard – the south Pacific. The increased push for critical infrastructure development, debt relief and financing has prompted the Australian government to initiate the ‘Pacific Step-up’ program, however, no one has stopped to ask: what is China’s end goal?

To continue reading the rest of this article, please log in.

Create free account to get unlimited news articles and more!

Like every ascendent economic, political and strategic power, China has used its period of rapid industrialisation and economic expansion to begin establishing its position within the broader global context – fuelled by a long memory of a "century of humiliation" at the hands of Western imperialism, finally ending with the successful Communist Revolution in 1949, China and its political leaders have dedicated the nation to establishing a new era of Chinese global primacy.

As China's position within the global order has evolved and its ambitions towards the Indo-Pacific in particular have become increasingly apparent, the Chinese government, driven by an extremely ambitious leader, President Xi Jinping, has identified a number of factors of both 'internal' and 'external' concern for the rising superpower's status.

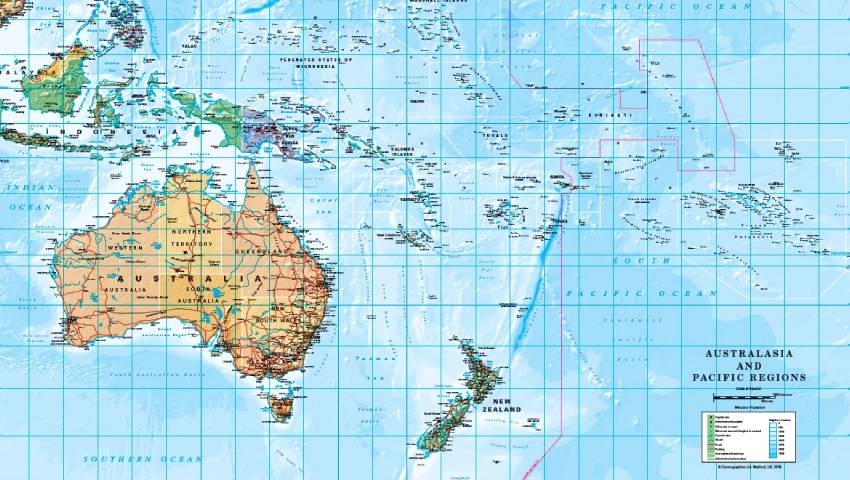

These 'concerns' extend to traditional areas of Chinese focus, namely central Asia, Tibet and the Taiwan situation, and more concerning for nations like Australia, the south Pacific and south-east Asia – further compounding these issues is America's resurgence, characterised by what China describes as: "intensified competition among major countries, significantly increased its defence expenditure, pushed for additional capacity in nuclear, outer space, cyber and missile defence, and undermined global strategic stability".

In response, the Australian government and Prime Minister Scott Morrison have kicked off the renewed 'Pacific Step-up' program to counter the growing economic, political and diplomatic influence of China as a result of the growing expansion of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – the Lowy Institute identified the growing power and influence China's BRI program has in supporting the Pacific.

"Infrastructure remains a crucial requirement for ensuring resilience in the Pacific. Considering the opportunities for collective engagement with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) merit careful analysis and discussion, particularly given that nine forum member countries have already signed bilateral memoranda of understanding to co-operate with China on the BRI," it said.

It is important to ask, what is the end goal of this program of influence development, what is the impact on Australia and is the 'Pacific Step-up' enough?

Endebted island nations and a mafia 'extortion racket'?

The Chinese people have long prided themselves as being students of history – the overt expansion of Chinese strategic capability and high-end military capability, particularly power projection forces, has drawn the attention of Australian, US and allied regional policy makers and strategic thinkers who have asked questions about the tactical and strategic intent behind the development of these forces.

Shifting the focus towards China's ambitious designs and infrastructure packages offered to a range of Pacific island nations including Papua New Guinea, Fiji and others – these nations represent incredibly small markets for Chinese produced consumer goods, with limited natural resources and are of limited if any strategic value in the event of conflict.

Japan learned the lesson of overreaching in the Pacific during the Second World War as the Pacific island hopping campaign strained the ability of the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces to adequately support and supply deployed forces throughout the far flung islands and coral atolls in the Pacific – once again raising the question, what is the end goal of China's infrastructure program?

It is equally important to take a closer look at the existing examples of China's BRI program and infrastructure financing programs as they have been rolled out throughout the Indo-Pacific and into Africa, with examples in Sri Lanka's Magampura Mahinda Rajapaksa Port located in Hambantota, which was financed by Chinese firms.

Looking to Africa, Chinese 'debt traps' in south-eastern Africa have resulted in the Chinese repossession of airports, mines, railways and similar infrastructure following the failure to service the loans by local governments – leaving these nations endebted to China with little to no control over their economic, political and strategic destiny.

An expansion of the South China Sea precedent?

Further compounding these 'internal issues' is the superpower's willingness to declare any area of economic, political or strategic interest a part of China, and nowhere is this more evident than in the South China Sea – placing the rising superpower's ambitions in direct conflict with the post-Second World War economic, political and strategic order established by the US and supported by a number of established regional powers, including Japan, Australia and South Korea.

China's White Paper clearly articulates its position towards the South China Sea and its construction of military facilities on reclaimed islands throughout the international waterways: "China resolutely safeguards its national sovereignty and territorial integrity.

"The South China Sea islands and Diaoyu Islands are inalienable parts of the Chinese territory. China exercises its national sovereignty to build infrastructure and deploy necessary defensive capabilities on the islands and reefs in the South China Sea, and to conduct patrols in the waters of Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea."

However, in late 2018 a Chinese colonel issued a stern warning to the US and its regional allies operating in the South China Sea and more broadly the western Pacific ocean where they may challenge China's increased territorial and economic ambitions throughout the regions.

Dr Malcolm Davis of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) told Defence Connect, "2018 has been an interesting year in the South China Sea. It started fairly early on with the basing of anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCM) on reclaimed islands in the SCS, the basing of the upgraded, H-6K nuclear-capable bomber on Woody Island and more recently the USS Decatur (DDG-73) incident really reinforces that China is not backing down from its territorial ambitions."

This growing assertiveness and apparent disregard for international convention and United Nations agreements places increased pressure on regional nations and the security paradigm upon which the stability of Indo-Pacific Asia is built.

China's bullying and intimidation tactics expand beyond direct military confrontation and thumbing their nose at international convention. The recent attempts by China to assert its influence and own wishes over ASEAN regarding the South China Sea Code of Conduct is particular evidence of this.

"What we saw recently with the ASEAN discussion about establishing a code of conduct for operating in the South China Sea was essentially a push by China to prevent all foreign navies from operating in the area. Given the amount of seaborne trade that flows through the South China Sea, that was obviously an unacceptable outcome for both the US and Australia," Dr Davis explained.

Questions for Australia

Despite Australia’s enduring commitment to the Australia-US alliance, serious questions remain for Australia in the new world order of President Donald Trump’s America, as a number of allies have been targeted by the maverick President for relying on the US for their security against larger state-based actors, which has seen the President actively pressuring key allies, particularly NATO allies, to renegotiate the deals.

Enhancing Australia’s capacity to act as an independent power, incorporating great power-style strategic economic, diplomatic and military capability serves as a powerful symbol of Australia’s sovereignty and evolving responsibilities in supporting and enhancing the security and prosperity of Indo-Pacific Asia. Shifting the public discussion away from the default Australian position of "it is all a little too difficult, so let’s not bother" will provide unprecedented economic, diplomatic, political and strategic opportunities for the nation.

However, as events continue to unfold throughout the region and China continues to throw its economic, political and strategic weight around, can Australia afford to remain a secondary power or does it need to embrace a larger, more independent role in an era of increasing great power competition? Further to this, without adding a degree of cynicism to the debate, what is China's end goal for this focus on Australia's backyard?

Get involved with the discussion and let us know your thoughts on Australia's future role and position in the US alliance structure and the Indo-Pacific more broadly in the comments section below, or get in touch with

Login

Login