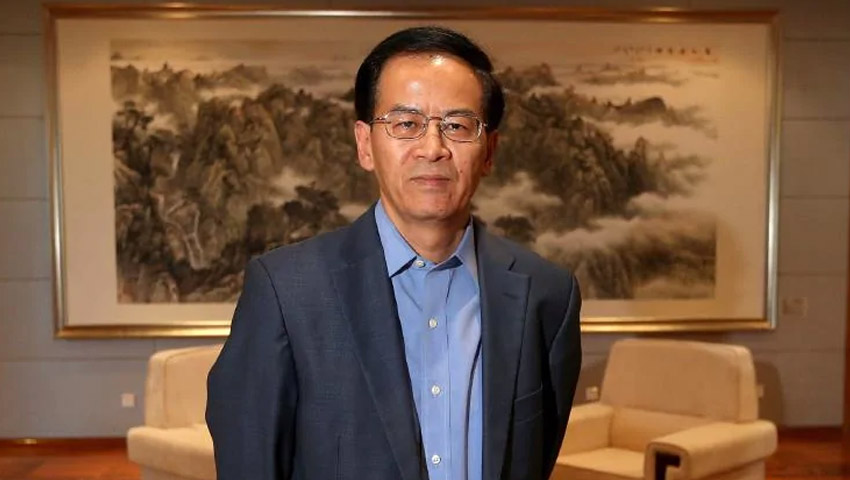

Beijing’s ambassador to Australia, Cheng Jingye, has called for greater “mutual respect” and a reduction of “prejudices and suspicions” specifically directed at Australia amid growing concerns about the rising power’s ambitions in the Indo-Pacific, making a pointed reminder about the intrinsic links between China’s economic miracle and Australia’s economic security.

Australia has enjoyed a record setting three decades of uninterrupted economic growth buoyed by the voracious appetite of a growing China, however all good things come to end as the political, economic and strategic competition between the US and China enters a new phase placing both the global and Australian economies in a precarious position.

Further compounding these emerging challenges is the growing period of economic and strategic competition between Japan and South Korea, equally important US and Australian allies, which have long-standing, robust links to Australia's economic security.

As this vortex of competition continues to devolve into a game of economic brinkmanship, resulting in trade tariffs and hindered supply chain access, many within Australia's political, economic and strategic policy communities have sought to redouble the nation's exposure to volatile and slowing economies.

Australia's earliest economic and strategic relationship with the British Empire established a foundation of dependence that would characterise all of the nation's future economic, defence and national security relationships both in the Indo-Pacific and the wider world.

As British power slowly declined following the First World War and the US emerged as the pre-eminent economic, political and strategic power during the Second World War – Australia became dependent on 'Pax Americana' or the American Peace.

The end of the Second World War and the creation of the post-war economic and strategic order, including the establishment of the Bretton Woods Conference, the International Monetary Fund and the United Nations, paved the way towards economic liberalisation and laid the foundation for the late-20th and early-21st century phenomenon of globalisation.

While the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War cemented America's position as the pre-eminent world power.

The changing economic order

This period was relatively short lived as costly engagements in Afghanistan and Iraq, peace-keeping interventions in southern Europe and enduring global security responsibilities have drained American 'blood' and 'treasure' – eroding the domestic political, economic and strategic resolve and capacity of the US to unilaterally counter the rise of totalitarian regimes and peer competitors in both China and Russia.

For example, since the white paper was released, China's share of global GDP has risen from 15 per cent to 20 per cent, based on purchasing power parity. India, the region's other emerging economic and industrial powerhouse, has seen its share of the global economy double from around 4 per cent to 8 per cent since the beginning of the 21st century, however the economic rise has given way to growing geo-strategic designs and competition throughout the region and is serving to unpick the fabric of the post-Second World War order.

From the South China Sea (SCS) to the increasing hostilities between India, Pakistan and China in the Kashmir region of the Himalayas, the Indo-Pacific's changing paradigm, and growing economic, political and strategic competition between the US and China, continued sabre rattling and challenges to regional and global energy supplies travelling via the Persian Gulf, and an increasingly resurgent Russia all serve to challenge the global and regional order.

Responding the growing "anti-Chinese sentiment"

China's seeming "economic miracle" and the subsequent push towards increased geo-strategic ambition throughout the Indo-Pacific raising concerns in nations across the region, including Australia, resulting in both the Chinese state-owned media and the large Chinese diaspora spread throughout the region to counter anti-Chinese sentiment.

Beijing's ambassador to Australia, Cheng Jingye, has issued a strong rebuke to growing domestic concern in Australia in a special interview with The Australian, during which Jingye reaffirmed China's commitment to "peaceful development" and a peaceful Chinese rise in the Indo-Pacific.

Despite the seeming benevolence of the Beijing's messaging, Jingye was quite pointed in his commentary about Australia and its economic dependence on China, stating: "You have been talking about your continuous economic growth, for the past 28 years. You have talked a lot about your trade surplus. It seems sometimes, some people forget what are the reasons behind that. China’s growth and the co-operation between China and Australia in trade, economic and other areas, is a major factor in that growth."

This pointed reminder of who pays who's bills is poignant for Australia's public policy makers, particularly regarding the nation's seeming over exposure to the Chinese economic miracle, placing it at an immense precipice, needing to pick between the US as Australia's strategic benefactor and China, the nation's primary economic partner.

What this fails to account for is that China's own economic growth and prosperity is equally dependent upon Australia's continuing benevolence in trading matters.

Nevertheless, Australia's seeming over exposure requires a course correction to prevent the nation from being overly exposed, but how does the nation achieve this?

An opportunity to hit the reset button

The economic emergence of the Indo-Pacific has presented the opportunity to re-write the nation's economic narrative, leveraging areas of natural competitive advantage, supporting the industrial reset with the birth of the fourth industrial revolution. Economic diversity and competitiveness is an essential component of enduring and sustainable national security.

However, this period of economic, political and strategic competition and brinkmanship provides interesting opportunities for Australian policy makers eager to navigate the economic, political and strategic competition of the region – the vast size and potential of Indo-Pacific Asia, particularly the economic opportunities and competition between global manufacturing hubs, the advent of Industry 4.0 and the new industrial revolution, combined with Australia's vast resource, energy and agricultural wealth serve as viable avenues for Australia to develop economic, strategic and political independence.

Undeniably China is an immense economic, political and strategic power – with a voracious appetite driven by an immense population and the nation positioning itself as the manufacturing hub of the world – however, beyond the 1.4 billion people, Indo-Pacific Asia is home to approximately 2.5 billion individuals each part of the largest economic and industrial transformation in human history.

Importantly, as Australia's traditional strategic benefactors continue to face decline and comparatively capable peer competitors – the nation's economic, political and strategic capability are intrinsically linked to the enduring security, stability and prosperity in an increasingly unpredictable region.

This period of unravelling relationships, seemingly fickle, transactionally focused strategic partners, economic slow downs and direct economic confrontation between allies all position Australia as a stable, reliable and responsible nation committed to the economic, political and strategic stability of the Indo-Pacific.

What this does require is a shift in the way in which the nation views not only itself, but also its position within the region – this also requires an opportunistic approach to the competition embroiling key allies like Japan and South Korea, and the global shift away from China driven by US President Donald Trump's continued pressure on companies with heavy operations in the rising power.

The rise of these economic powerhouses – driven by a combination of increased resource, energy and consumer goods consumption and the development of an advanced domestic manufacturing base – places Australia in both an opportune and precarious position, as the growing economic wealth has translated to increased demand for resources, energy, agricultural and consumer goods, but also increased investment in defence capability.

Australia as a nation, like many Western contemporaries, has been an economy and nation traditionally dependent on heavy industries – capitalising upon the continent's wealth of natural resources including coal, iron ore, copper, zinc, rare earth elements and manufacturing, particularly in the years following the end of the Second World War.

However, the post-war economic transformation of many regional nations, including Japan, Korea and China, and the cohesive, long-term nation building policies implemented by these nations has enabled these countries to emerge as economic powerhouses, driven by an incredibly competitive manufacturing capability – limiting the competitiveness of Australian industry, particularly manufacturing.

Recognising this incredibly competitive global industry and the drive towards free trade agreements with nations that continue to implement protectionist policies buried in legislation, Australia needs to approach the development of nationally significant heavy industries in a radically different way, recognising the failures and the limitations of Australia's past incarnations of heavy industry.

Your thoughts

The nation is defined by its relationship with the region, with access to the growing economies and to strategic sea-lines-of-communication supporting over 90 per cent of global trade, a result of the cost-effective and reliable nature of sea transport.

Indo-Pacific Asia is at the epicentre of the global maritime trade, with about US$5 trillion worth of trade flowing through the South China Sea and the strategic waterways and chokepoints of south-east Asia annually.

For Australia, a nation defined by this relationship with traditionally larger, yet economically weaker regional neighbours, the growing economic prosperity of the region and corresponding arms build-up, combined with ancient and more recent enmities, competing geopolitical, economic and strategic interests, places the nation at the centre of the 21st century's 'great game'.

Enhancing Australia’s capacity to act as an independent power, incorporating great power-style strategic economic, diplomatic and military capability serves not only as a powerful symbol of Australia’s sovereignty and evolving responsibilities in supporting and enhancing the security and prosperity of Indo-Pacific Asia. Shifting the public discussion away from the default Australian position of "it is all a little too difficult, so let’s not bother" will yield unprecedented economic, diplomatic, political and strategic opportunities for the nation.

Get involved with the discussion and let us know your thoughts on Australia's future role and position in the Indo-Pacific and what you would like to see from Australia's political leaders in terms of shaking up the nation's approach to our regional partners, and the avenues Australia should pursue to support long-term economic growth and development in support of national security in the comments section below, or get in touch with