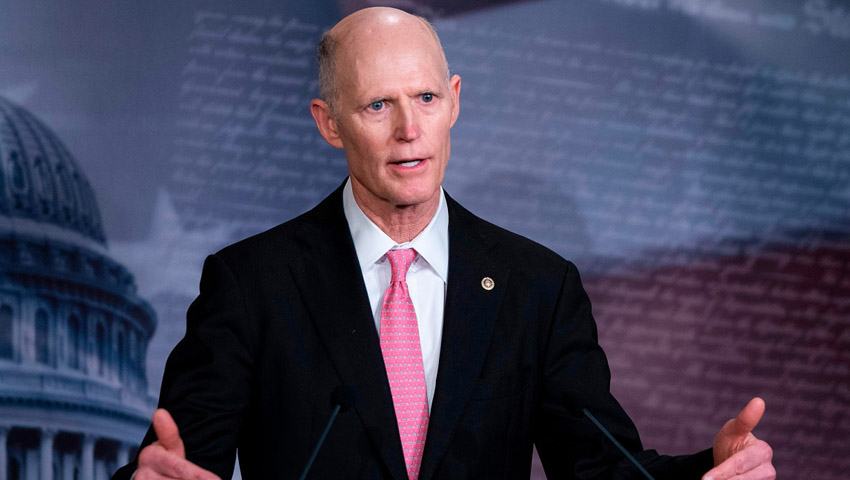

Influential Republican senator Rick Scott has urged democracies, including Australia, to counter Beijing’s emboldened post-COVID pursuit of “world domination”, citing shared values across the economic, political and strategy spectrum.

Australia has long been torn between balancing its own interests and security agenda and that of larger, “great” and “powerful” friends like the British Empire and the US.

Now in the post-COVID era, great power competition appears to have emerged as a major challenge to the nation’s future defence and national security agenda.

While the nation’s history of strategic policy has evolved a great deal since the end of the Second World War – when the nation was once directly engaged in regional strategic and security affairs, actively deterring aggression and hostility in Malaya during the Konfrontasi and communist aggression in Korea and Vietnam as part of the “Forward Defence” policy.

Growing domestic political changes following Vietnam saw a dramatic shift in the nation’s defence policy and the rise of the “Defence of Australia” doctrine – this doctrine advocated for the retreat of Australia’s forward military presence in the Indo-Pacific and a focus on the defence of the Australian continent and its direct approaches.

This shift towards focusing on the direct defence of the Australian mainland dramatically altered the nation’s approach to intervention in subsequent regional security matters, significantly impacting the capacity of Australia to carry out concurrent stabilising operations throughout the region.

These included Australia’s intervention in East Timor and later, to a lesser extent, in the Solomon Islands and Fiji during the early to mid-2000s while the Australian Defence Force juggled concurrent, ongoing operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, exposing the limitations of the Vietnam-era doctrine and resulting force structure.

Each of these missions were further followed by subsequent ad hoc humanitarian and disaster relief deployments throughout the region, each further stretching the ADF’s capacity to juggle multiple concurrent operations.

Further complicating the nation’s strategic capabilities is the evolution of modern warfare, with high-tempo, manoeuvre-based operations that leveraged the combined capabilities of air, sea, land and space forces to direct troops, equipment and firepower around the battlefield, yielding to low-intensity humanitarian and peacekeeping operations in southern Europe and the south Pacific, and the eventual rise of asymmetrical, guerilla conflicts in the mountains of Afghanistan and streets of Iraq.

Adding further disruption to Australia’s post-Cold War strategic assessments, doctrine and force structure is the rise of China as a peer or near-peer competitor, combined with a resurgent Russia, recalcitrant Iran and myriad traditional and asymmetric challenges.

Each of this individual factors is further compounded by the impact of COVID-19 on the established economic, political and strategic order, while we wait for the dust to settle and the true impact of the global pandemic to be known, Beijing has made a series of moves throughout the Indo-Pacific, demonstrating its willingness to directly assert its interests.

Discussing the simmering tensions between Washington and Beijing with the Sydney Morning Herald, influential Republican senator Rick Scott has urged all democracies, but particularly Australia, to step up their pressure on China.

World domination is the goal, no doubt about it

Setting down the gauntlet, Senator Scott said, “Every democracy needs to stand up for what they believe in. If you believe in fair trade, that’s not what China believes in. If you believe in human rights, that’s not what China believes in.

“They believe in world domination by the Communist Party of China. The way I look at it is that the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party [Xi Jinping] has made a decision to have a cold war against the United States and democracies around the world.”

This provocative language from Senator Scott echoes similar sentiments from the US Commander of Indo-Pacific Command, Admiral Philip Davidson, earlier this year.

Australia’s economic dependence upon China places the nation in an increasingly vulnerable position, challenging the economic, political and strategic sovereignty of the nation and is something that ADML Davidson clearly articulated during an address to the Lowy Institute.

ADML Davidson explained, “Beijing has shown a willingness to intervene in free markets and to hurt Australian companies simply because the Australian government has exercised its sovereign right to protect its national security.”

While economic in nature, this relationship between Australia and China places the nation in a state of “strategic dependence” on Beijing, limiting Australia’s economic, political and strategic sovereignty and the potential response to mounting Chinese assertiveness in the South China Sea and increasingly further into the Pacific.

This is something that ADML Davidson explained in detail as insidious and undermining in its nature, saying, “Beijing’s approach is pernicious. The party uses coercion, influence operations and military and diplomatic threats to bully other states to accommodate the Communist Party of China’s interests.”

Evidence of this can be seen from the South China Sea and Beijing’s repeated belligerence in the area, through land reclaimations and the militarisation of island fortresses in defiance of international condemnation, and increasingly assertive maritime and aerial interdiction operations throughout the region, bringing China’s armed forces into direct confrontation with US, Japanese, Australian and other allied forces.

Further challenging Australian and US policymakers is the pervasive expansion of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative and “debt diplomacy”, which has already seen disastrous results for developing nations from Africa to the Pacific, with Beijing taking direct control of key strategic and economic assets, including mines and airports to major maritime hubs like Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka.

Closer to home, repeated rumours about China’s plans to establish a major naval base in Fiji or the Solomon Islands serve as powerful reminders that Australia is at the epicentre of the new “Cold War”.

Senator Scott added, “We ought to do this together. All democracies are going to have to say to themselves: Are they going to continue to appease the Communist Party of China, which is clearly focused on world domination and has taken jobs from democracies all over the world and stolen technologies from all over the world?”

The ‘defining strategic challenge of our time’

It is important to recognise that for the first time, America has a true competitor in China – a nation with immense industrial potential, growing wealth and prosperity, a driving national purpose and a growing series of alliances with re-emerging, resource-rich great powers in Russia.

Unlike the Soviet Union, China is a highly industrialised nation – with an industrial capacity comparable to, if not exceeding, that of the US, supported by a rapidly narrowing technological gap, supporting growing military capability and territorial ambitions, bringing the rising power into direct competition with the US and its now fraying alliance network of tired global allies.

Recognising this, ADML Davidson articulated the need for recognition of this great power competition, telling Sky News’ Kieran Gilbert:

“I would say the defining strategic challenge of our time is indeed China and its very pernicious approach to the region in all aspects, whether it is the way they provide developmental funds, the diplomatic cohesion they put on others, their activities in the South China Sea and the very disruptive ways that they use their economy to punish others when they don’t like what others are doing.”

Senator Scott praised Australia’s position and commitment to holding Beijing to account amid the global economic crisis ensuing from the COVID-19 pandemic, stating that Australia’s commitment to the post-Second World War order was consistent with the unique relationship between Australia and the United States.

“What I admire about Australians is they will stand for their convictions. Australia, like America, has been working to hold China accountable. We’ve got to find out what happened here, why it happened and make sure it doesn’t happen again.

“I’m very appreciative of Australia’s push to get the facts, live in reality and hold people accountable for their actions.

“One decision that is not difficult is to always stand with our Australian mates. No matter the external pressure or coercion, we will always have Australia’s back, just as Australia has always had ours,” Senator Scott added.

Your thoughts

Australia’s position and responsibilities in the Indo-Pacific region will depend on the nation’s ability to sustain itself economically, strategically and politically.

Despite the nation’s virtually unrivalled wealth of natural resources, agricultural and industrial potential, there is a lack of a cohesive national security strategy integrating the development of individual yet complementary public policy strategies to support a more robust Australian role in the region.

Enhancing Australia’s capacity to act as an independent power, incorporating great power-style strategic economic, diplomatic and military capability serves as a powerful symbol of Australia’s sovereignty and evolving responsibilities in supporting and enhancing the security and prosperity of Indo-Pacific Asia.

Shifting the public discussion away from the default Australian position of “it is all a little too difficult, so let’s not bother” will provide unprecedented economic, diplomatic, political and strategic opportunities for the nation.

However, as events continue to unfold throughout the region and China continues to throw its economic, political and strategic weight around, can Australia afford to remain a secondary power or does it need to embrace a larger, more independent role in an era of increasing great power competition?

Further complicating the nation’s calculations is the declining diversity of the national economy, the ever present challenge of climate change impacting droughts, bushfires and floods, Australia’s energy security and the infrastructure needed to ensure national resilience.

Let us know your thoughts and ideas about the development of a holistic national security strategy and the role of a minister for national security to co-ordinate the nation’s response to mounting pressure from nation-state and asymmetric challenges in the comments section below, or get in touch with