Despite an increasingly unstable Indo-Pacific and strained intra-Korean dialogue, it is far from certain that South Korea will align itself closer to the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue. Considering the country’s close economic ties to China, coupled with deep historical and political grievances between Japan and South Korea, will South Korea maintain its policy of strategic ambiguity toward Taiwan?

To continue reading the rest of this article, please log in.

Create free account to get unlimited news articles and more!

Strained relations on the Korean peninsula

Earlier this week, intra-Korean dialogue strained yet further as North Korea trialled the launch of a second ballistic missile in two weeks. While the rogue state claims that the launch of the initial missile on 5 January was a test of the country’s new hypersonic weapons system, South Korea’s intelligence community downplayed the subtle threats of their northern neighbours.

The most recent launch was a shot across the bow as members of the United Nations Security Council, including the US, Albania, France, Ireland and the UK – additionally supported by Japan – rebuked the country for its purported “hypersonic missile” trial, urging North Korea to halt its nuclear weapons and missile development regime.

Over recent weeks, Australia also joined its international partners in applying further pressure to the rogue state, with the Australia-Japan Reciprocal Access Agreement reaffirming the partnership’s commitment to peace on the Korean peninsula.

“The two leaders condemned North Korea’s ongoing development of nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles, reiterating their commitment to achieving the complete, verifiable and irreversible dismantlement of all nuclear weapons, other weapons of mass destruction, and ballistic missiles of all ranges of North Korea,” the joint statement by the prime ministers of Australia and Japan read.

Beyond North Korea’s posturing, the rogue state has been executing an ongoing grey zone campaign against their southern neighbours. In 2013, it was reported that the North Korean-sponsored Lazarus Group caused an estimated $750 million in damage to South Korean infrastructure, disabled ATMs and stole the details of some 20,000 South Korean military personnel.

Facing a destructive and belligerent neighbour to the North whose political, economic and military leadership closely aligns with Beijing, one would assume that South Korea’s natural partnerships align firmly with the new Quadrilateral Security Dialogue.

As of yet, this remains to be seen.

South Korea remains economically reliant on China and has demonstrated little willingness to tempt Chinese economic reprisals unlike Japan, India and Australia. According to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (albeit still using 2019 data), China is South Korea’s largest export destination, representing 25 per cent of the nations exports. This figure almost doubles the 13.5 per cent represented by the United States sitting in second place. Meanwhile, China represents 21.3 per cent of the country’s imports, again compared with the 12.3 per cent of the US at number two.

It is easy to sympathise with South Korea’s hesitation toward economic reprisals. In 2017, China restricted trade and tourism to the country in response to its installation of the US Terminal High Altitude Area Defense missile interceptor (THAAD), which reportedly gave radar intelligence deep into China’s interior. South Korean industry was dealt a devastating blow by the Chinese sanctions.

Moreover, while public attitudes toward the United States in South Korea remain warm, such positive sentiment isn't felt toward all members of the Quad. Public sentiment toward Japan in South Korea remains incredibly low following centuries of hostilities between the two neighbours. Recent opinion research published by Hankook Research showed that for the first time since the survey’s inception in 2018 that South Koreans rated China less favourably than Japan. While Japan recorded a 28.8 per cent favourability rating, North Korea and China were rated at 28.6 per cent and 26.4 per cent, respectively. It would suggest that there is little support for the Republic of Korea to support either China or Japan in the event of major hostilities.

While to the regular observer it may appear that South Korea is a natural bedfellow of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, the historic, economic and political dimensions heeding rapprochement between Japan and South Korea are overwhelming. In this light, how does this impact South Korean policy to the Taiwan flashpoint?

Japan, Australia and the US begin to abandon strategic ambiguity on Taiwan, will South Korea follow?

Australia, Japan and the US have long straddled a policy of ambiguity on the question of Taiwanese sovereignty.

At the outbreak of the Sino-Soviet split, when cracks began to appear between the USSR and China on the question of which country would form the global communist vanguard, the US implicitly aligned itself closer to China to mitigate the growing hegemony of the Soviets.

It wasn’t so long ago that the US even tacitly worked with China on military and intelligence matters, evidenced throughout the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan when clandestine intelligence units in the US and China would implicitly trade intelligence with one another to the detriment of the USSR.

Now with little need to placate China, the policy of strategic ambiguity has gone by the wayside.

While official foreign policy doctrine is sluggish to confine strategic ambiguity to history, Australia, Japan and the US’ political leadership has been forthright on their willingness to defend Taiwan. President Biden event went as far as to suggest that the United States has a commitment to defend Taiwan, notions of which were echoed by Australia’s Defence Minister Peter Dutton and an agreement between the US and Japan to use the island of Kyushu as a staging area for the deployment of troops in the region.

The Republic of Korea, on the other hand, has been far more silent on the issue.

Writing in War on the Rocks this month, Professor Sungmin Cho of the Daniel K. Inouye Asia Pacific Center for Security Studies argued that despite generic promises to protect peace in the region between the US and South Korea, that the Korean government has sought to downplay any existence of bilateral military co-operation between Taiwan and the Republic of Korea.

PROF Cho notes that despite simply agreeing to harmony in the Taiwan Straits, that “in the domestic briefing on the outcome of the summit, however, South Korean Foreign Minister Chung Eui-yong remarked, ‘We are fully aware of the unique relations between China and Taiwan. Our government’s stance has not changed. We’d like to reiterate that regional peace and stability is the common wish shared by everyone in the region.’”

The analyst remarks that despite the close ideological, political and economic affinities between North Korea and China, the two countries also seek the same end goal: political reunification with a land and population that they perceive to be legally theirs. If either China or North Korea seeks to undertake military action, the other could militarily act in to support the broader goal of reunification or to suppress US military capabilities.

“Despite the difference in legal status, Chinese experts tend to positively perceive that Korean unification, if it happens first, would stimulate the Chinese people’s aspiration for national unification. They even expect that Beijing may learn some lessons from the Korean experiences of integrating two different systems.

“Therefore, if Pyongyang intends to do so, Beijing will not oppose North Korea’s concurrent provocations to pin down US Forces Korea and US Forces Japan from moving to the Taiwan Strait.”

As such, while the South Korea’s apprehension toward involvement in the Taiwan Strait is economically justifiable, Professor Cho notes that any military activity in the region could likely cascade to involve a vector of North versus South Korean conflict regardless of their position of strategic ambiguity toward Taiwan.

Though, over recent weeks – signals from Seoul show little sign of support to Taipei regarding the Taiwan Straits question.

In late December, South Korea disinvited Taiwan’s Digital Minister Audrey Tang from taking part in a business conference in the country. The invitation to speak was cancelled regarding “cross-Strait issues.”

In response, Taiwanese spokeswoman noted that "the foreign ministry has summoned the South Korean acting representative to Taipei to express our strong dissatisfaction over the impolite action”.

South Korea supporting Australia’s defence industry

Despite ongoing strategic ambiguity regarding the Taiwan Strait, Seoul has sent positive signals to Australia’s defence industry co-operating on a wide range of cutting-edge upgrades for the war fighting capabilities of the Australian Defence Force.

Last month, South Korea-based defence company Hanwha signed a $1 billion contract with the Commonwealth government for the supply of Huntsman self-propelled artillery systems and armoured ammunition resupply vehicles to the Australian Army under the LAND 8116 Phase 1 program.

The vehicles are set to be manufactured in Australia at a new facility operated by the firm’s local Victoria-based facility.

Just days later, Australia and South Korea formally committed to bolstering co-operation in the space domain under a new collaboration agreement.

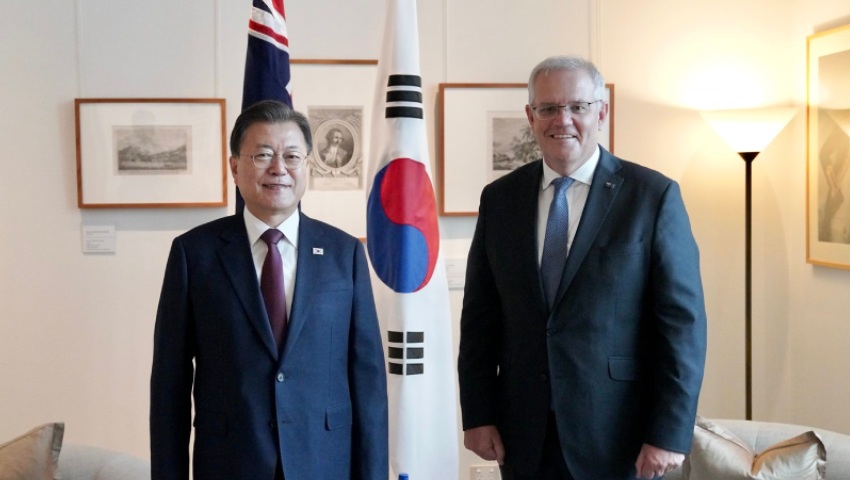

The announcements coincided with South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s fourth meeting with Prime Minister Scott Morrison, signalling a shift in the nature of Canberra and Seoul’s long-standing relationship.

Prime Minister Morrison, who was joined by President Moon at a signing ceremony at Parliament House in Canberra to announce the Hanwha deal, noted the importance of the nations’ Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, adding that bolstering industry collaboration would support efforts to address “mutual security challenges”.

Meanwhile, after signing the space MOU with Australia, President Moon said he hoped the deal would “enhance exchange and foster co-operation” across a range of fields including space exploration, the launch vehicle industry, and satellite navigation.

“[I] hope this agreement [becomes] the stepping stone for the two countries to expand into space together,” President Moon added.

According to Michael Shoebridge, ASPI’s director defence, strategy and national security program, such initiatives form part of South Korea’s new regional security strategy.

“In sheer strategic and defence terms, South Korea shifted from its sole focus on the threat from North Korea several years ago and has been pursuing a force structure for its military that is able to play a part in deterring conflict in the wider region,” he writes.

“Seoul is showing strategic imagination that’s being translated into real military capability in a timely way.”

Shoebridge points to the country’s push to develop surface and sub-surface capabilities, aimed at strengthening its offensive posture.

He also notes South Korea’s aircraft carrier program, which would support longer-range regional engagements.

Other areas of investment include a ramp up in the development of independent surveillance and reconnaissance, and precision strike capabilities, which have “broader application than only deterring Pyongyang”.

“All these developments provide a platform for defence-to-defence cooperation from research and development to operational concepts and shared capabilities between Australia and South Korea,” Shoebridge continues.

But “high-technology” co-operation should be at the core of the partnership.

This, he writes, should include low-emissions technologies, space, critical-minerals, semi-conductors, artificial intelligence and uncrewed systems.

Shoebridge suggests Hanwha Defense Australia’s potential receipt of the LAND 400 Phase 3 contract — an $18 billion to $27 billion program to deliver next-generation infantry fighting vehicles to the Australian Army — could help get the ball rolling.

“Australia would have to build a deep technical working relationship with South Korean industry and its government research and development efforts, and this relationship could be used for co-operation on more useful capabilities that both countries need like missiles, small satellites, new energy systems for military purposes and unmanned systems,” he writes.

“That’s an indirect way to extract value from a dubious army armoured vehicle program, but if it’s really going to proceed, then it makes sense to extract benefits out of it that matter to our strategic environment.”

South Korea’s geostrategic pivot and its efforts to ramp up industry collaboration with regional partners like Australia signal “some alignment” on the “bigger strategic picture” around the Quad, AUKUS and shared challenges posed by China.

However, Shoebridge notes that while Seoul would benefit from co-operatives like the Quad and AUKUS, it would explore non-government alternatives to fostering its relationship with like-minded neighbours.

He suggests Prime Minister Morrison invite his counterpart to the 2022 Sydney Dialogue on emerging and critical technologies.

“If we understand our strategic environment and the future of our digital world as it is affected by this, the future of the relationship won’t be about South Korea equipping the Australian Army with tracked howitzers and large armoured fighting vehicles,” he writes.

“Instead, it will be through deeper cooperation in the areas of strength that South Korea’s defence organisation and military are pursuing and that are relevant to maritime and air power, missiles, space and strike capabilities.

“And in a bigger strategic way, it will be through the contribution that the unique partnership between South Korea’s government and its ‘big tech’ sector can make to how the world’s powerful and creative democracies can harness the digital world for common prosperity, security and [wellbeing].”

Your say

Low public sentiment for Korean-Japanese relations and an economic incentive to remain neutral in the era of US vs Chinese hegemony in the region are factors to evidence South Korean ambiguity.

Should the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue make greater overtures to South Korea and create larger trading blocks to mitigate Chinese economic reprisals and reverse the low Korean-Japanese public sentiment?

As always, provide your thoughts in the comments below.

Get involved with the discussion and let us know your thoughts on Australia’s future role and position in the Indo-Pacific region and what you would like to see from Australia's political leaders in terms of partisan and bipartisan agenda setting in the comments section below, or get in touch with

Login

Login