Will the 46th president reassert the United States’ presence in the global arena, or will internal challenges stifle his policy agenda?

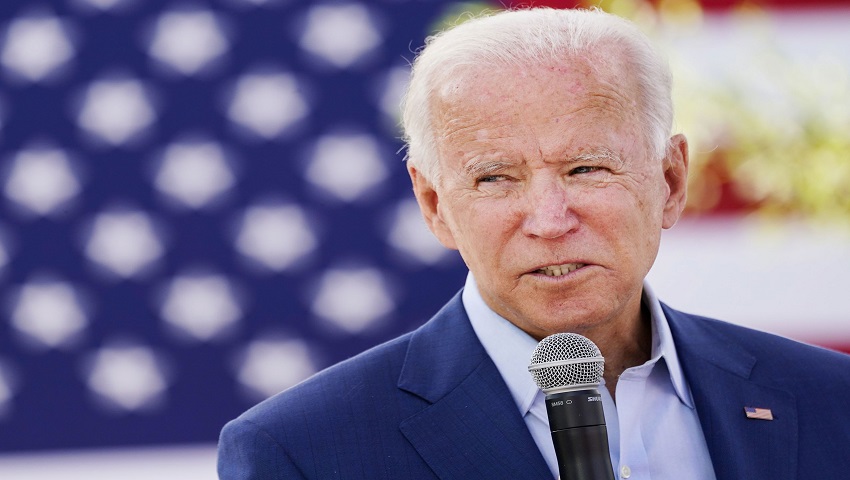

According to Dr Gorana Grgic, lecturer in US politics and foreign policy at the United States Studies Centre (jointly appointed with the Department of Government and International Relations, University of Sydney), US President Joe Biden has a “hefty task” of convincing both compatriots and the broader international community that the US can still lead on the world stage.

Dr Grgic notes that Biden’s foreign policy team — mostly consisting of Obama-era alumnus — has reverted to an emphasis on diplomacy, multilateralism and value-based leadership — flags waved by previous Democratic administrations.

However, Dr Grgic adds that President Biden would face a unique set of challenges, which may curtail efforts to redirect US foreign policy.

“Biden’s foreign policy will be more constrained by situational factors at home and abroad. Deep political divisions and multiple crises — emerging from or amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic — will limit his presidential attention and action,” she writes.

“And as the world grows more unstable, uncooperative and illiberal, US foreign policymakers will have significantly less room to manoeuvre.”

Dr Grgic also observes that while President Biden has sought to differentiate himself from his predecessor on issues such as climate change, global health and arms control, he has “inherited competitive disposition towards China”.

“[China] has made it abundantly clear that economic statecraft will remain a vital aspect of its strategy,” she notes.

“Yet, there is uncertainty around the policy specifics, much of which will hinge on contingency planning and bureaucratic politics.”

The University of Sydney lecturer goes on to point out the ideological divide within the Biden administration, over “traditional and non-traditional security issues”.

“On one hand, there are those who believe the greatest threats to the United States are of primarily kinetic origin. On the other, there are those who argue the largest threats are anthropogenic,” she continues.

“The former argue that the United States should maximise its military and economic capabilities to compete with China. The latter maintain that climate change is the mother of all questions that can only be addressed if the world’s two largest economies work together.”

Dr Grgic also notes the generational divide among senior members of the executive branch.

“The President’s younger appointees generally advocate for a more assertive response to China, while the older guard are wary of a new Cold War,” she adds.

Finally, Dr Grgic stresses the “decisive impact” of “bureaucratic and domestic politics” on the overall trajectory of US foreign policy.

“The Obama years are a telling example of the long road between strategic planning and policy implementation,” she observes.

“Obama began his first term with a dovish outreach to China, but as China appeared to grow more assertive the more hawkish response advocated by the State Department became the preferred policy.

“The infamous ‘pivot to Asia’ was never fully implemented because US domestic politics and partisanship got in the way of ratifying the Trans-Pacific Partnership, and attention to seeing through this agenda in Obama’s second term shifted with the reprioritisation of the Middle East and Europe.”

Dr Grgic concludes by noting that while President Biden has employed tough rhetoric on China in his first few months in office, the coming months would reveal whether rhetoric would be matched by a policy response.

Get involved with the discussion and let us know your thoughts on Australia's future role and position in the Indo-Pacific region and what you would like to see from Australia's political leaders in terms of partisan and bipartisan agenda setting in the comments section below, or get in touch with

Login

Login