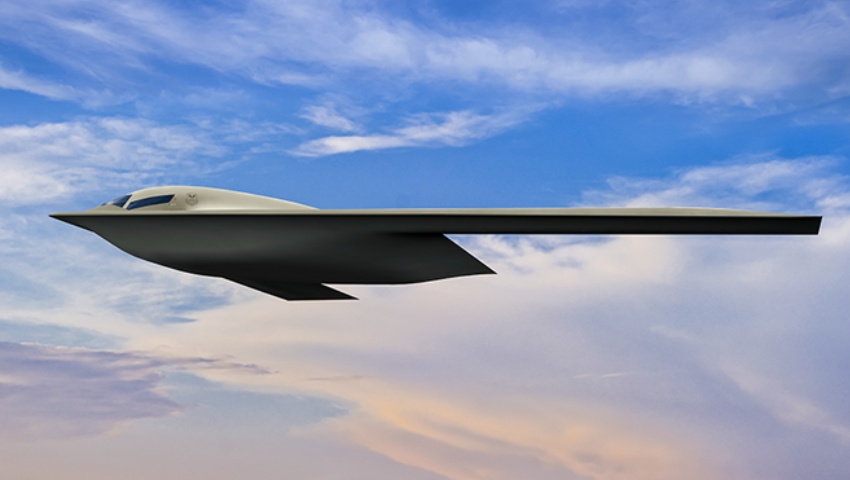

The B-21 is expected to be the world’s most advanced, cost-effective long-range strike capability. With recent technology sharing arrangements in place under the AUKUS agreement, Australia must make the case to our US allies to procure B-21s and to house one of the world’s most fearsome deterrents right in our airbases.

The technology sharing arrangements underpinning the AUKUS partnership evidence a derogation in longstanding US defence policy. The liberal democratic world, with the US at its epicentre, has maintained global security through the qualitative superiority of US military hardware thus acting as a deterrent against acts of aggression and outright armed conflict.

Willingness for the US to undertake technology sharing arrangements, indeed technology as sensitive as nuclear-powered submarines, illustrates that the US is eager to bring its allies into the tent to mitigate the country’s quantitative disadvantages and the slow decline of their qualitative edge. Simply, qualitative deterrence is no longer sufficient.

This week, headlines of China's recent hypersonic missile test beamed on television and computer screens the world over:

"China tests physics-defying weapon near Aus" - News.com.au

"China’s hypersonic missile test ‘close to Sputnik moment’, says US general" - The Guardian

"US is ‘years behind’ China on hypersonic weapons, Raytheon head says" - South China Morning Post

The Clausewitzians among us observe that war is a continuation of politics by other means. "Each strives by physical force to compel the other to submit to his will: his first object is to throw his adversary, and thus to render him incapable of further resistance," the great theorist wrote.

Possessing neither a quantitative or qualitative edge, how can the US compel others to support the global rules-based order?

Introducing the B-21

While most of the B-21’s capabilities remain hushed in secrecy – open to few outside the Pentagon and Northrop Grumman – domiciling the aircraft’s long-range strike capabilities will heavily tilt the balance of power in the Indo-Pacific.

Analysts’ hypotheses of the B-21’s capabilities range from logical to fanciful. While some sources suggest that the B-21 will be able to travel anywhere on the world, even more measured analysts such as ASPI’s Marcus Hellyer suggest that the B-21 would increase Australia’s strike range at least threefold.

“It’s using two F-35 engines, for example, but it will have three or four times the range of the F-35. That will allow it to reach far out into the Indo-Pacific, greatly complicating the planning of any adversary operating against us or our friends. It also means it can be based deep inside Australia, far from threats, and still not need to rely on tanker support,” Hellyer wrote in ASPI’s The Strategist.

In such an expansive region as Australia and the Indo-Pacific, Hellyer outlines that Australia's current fleet of F-35A jets do not currently meet the requirements for strike missions in the event of a potential conventional war in the region as the systems can only operate in a 1,000-kilometre radius – shorter than the striking distance of modern Chinese missile systems.

In his analyses of the B-21, Hellyer reinforces a critical point. The increased range of the B-21 allows the RAAF to tuck the aircraft safely away in Australia’s interior, further from the strike capacity of any potential enemies. Such capabilities will allow Australia to expand its umbrella of deterrence over the Indo-Pacific, safely encompassing Australia’s key regional allies under a Pax Australis.

The announcement of technology sharing arrangements as part of the AUKUS partnership have set an optimistic precedent for burden sharing between the two nations. Indeed, there is no shortage of reasons as to why the US should embark upon further technology sharing capabilities.

Firstly, enabling Australia to operate a regional deterrence umbrella underpinned by both B-21s and nuclear-powered submarines would enable the US to efficiently allocate troops. While Marine rotations in Australia’s Top End is a welcome gesture and necessary for regional stability, long-range strike options would allow the US to station troops in more important regional theatres. Recently, this was evidenced with Russian troop build ups on the boarder of Ukraine and military exercises in Belarus. With energy coercion from Moscow and British troop cuts, there is little evidence that the United States’ NATO partners have an appetite to support the international rules-based order.

Secondly, in the face of inflation and economic instability, burden sharing will allow the US to ensure the ongoing war readiness of its military apparatus in more fundamental areas: troop pay, and technology development. Recently, Marcus Weisgerber in Defense One noted, “The biggest inflation spike in three decades has the Pentagon bracing for salary increases and more expensive weapons, according to current and former defence officials.” As such, technology sharing with one of the US’ closest allies will ensure that the US military can go back to basics and make sure that soldiers are paid and military technology makes its way to war fighters.

So far, it appears as though the B-21 technology is currently on track. It is expected that the first B-21 will be finished in early 2022, and complete its first flight shortly after. If all is successful during this phase, the B-21s will likely be rolled out to the US Air Force in the mid-to-late 2020s.

While Chinese sources have claimed that they have developed unmanned aerial systems that can rival the B-21, some analysts have rubbished these claims.

“The Feilong-2 (“Flying Dragon 2”) long-range combat drone is a bomber-like aircraft that its developer, Zhongtian Feilong Intelligent Technology of X’ian, China, says nears the B-21 in some ways and is better in others, making it effectively just as good. The claim is, simply put, preposterous,” Kyle Mizokami wrote in Popular Mechanics.

Interestingly, the price of the B-21s isn’t even particularly prohibitive. “A squadron of 12 aircraft will likely total around $20-25 billion once we add in bases, support systems such as simulators and maintenance facilities, and so on. That’s a lot, but compared to the $45 billion to be spent on future frigates, the $89 billion on submarines or indeed the $30 billion on armoured vehicles, it’s a price worth considering,” ASPI’s Hellyer wrote in The Strategist.

Get involved with the discussion and let us know your thoughts on Australia's future role and position in the Indo-Pacific region and what you would like to see from Australia's political leaders in terms of partisan and bipartisan agenda setting in the comments section below, or get in touch with

Login

Login