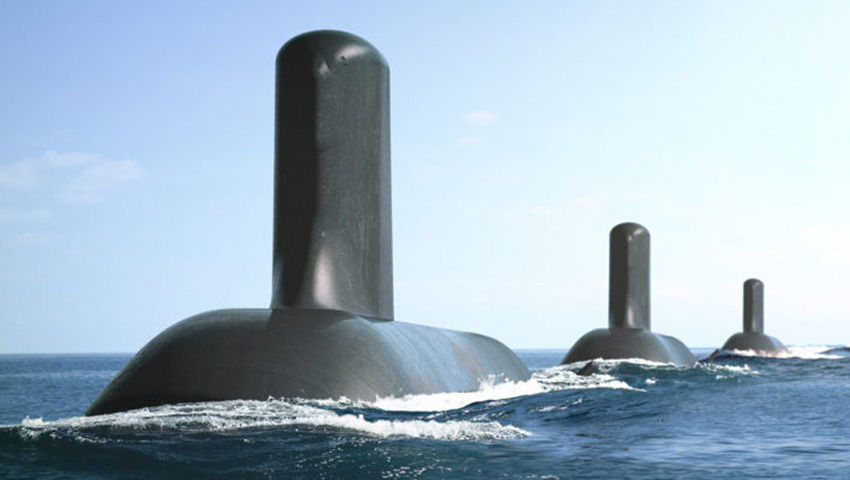

France recently announced it had reached agreement with India to develop six nuclear attack submarines (SSN) for the Indian Navy.

To continue reading the rest of this article, please log in.

Create free account to get unlimited news articles and more!

This follows Indian experience with the leasing of an Alfa Class SSN from Russia and the indigenous development of nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines of the Arihant (SSBN-80) Class.

For Australia, this represents an extraordinary opportunity to articulate a long-term strategy for Australian SSN submarine acquisition to follow the currently running Attack Class future submarine program that will replace the current Collins Class after extension of their service life by a decade in the so-called life-of-type-extension (LOTE).

The Attack Class program currently calls for 12 boats to be delivered over a protracted period extending through 2054, more than a generational epoch in which society will change dramatically due to technology, geopolitics, pandemics, climate change and other as-yet unknown influences.

It behoves us therefore to envisage changes to current planning to accommodate the societal changes and within this ambit there must be consideration of nuclear power as an emissions-free energy source.

Why is this relevant to submarines?

The popular belief is that a nuclear power industry is an essential pre-requisite for nuclear propulsion to be adopted for Australian submarines or other vessels requiring greater endurance and speed such as icebreakers or high-speed freight liners.

This view has been disputed in recent publications notably the recent book An Australian nuclear industry. Starting with submarines? edited by Professor Tom Frame of UNSW Canberra and published by Connor Court, and by retired Navy Commodore Denis Mole in his article ‘Nuclear submarines could lead to nuclear power for Australia’ published by ASPI in The Strategist.

So, how would the nuclear submarine roadmap unfold?

Firstly, the current relationship between Australia and France for the Attack Class needs to be revised to reflect the possibility that the class may be superseded by a nuclear submarine class in the future and this possibility should be taken into consideration but never allowed to slow down the current program as it is already a matter of urgency.

Secondly, there must be consideration for a dialogue with India to propose collaboration in the future such that Australia may learn from both France and India on the way ahead when Australia is starting from such a low level of experience of nuclear power.

This is not to understate the critical roles to be played by the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO) as a source of science and technology knowledge and of the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency (ARPANSA) for regulatory oversight.

However, if Australia follows the practice of the US and UK there will need to be established an additional authority for naval reactors as they are required to meet additional criteria for operational performance such a shock-resistance and sustainability, such as much longer periods between refuelling of nuclear reactor fuel. In addition, there would need to be a fundamental investment in education, training and qualification of all personnel engaged in any aspect of the nuclear fuel cycle in Australia.

The exceptional safety record of nuclear propulsion in the US, UK and France has not been accidental.

For the US Navy and the UK Royal Navy this has been a direct result of the highly rigorous approach taken by the father of nuclear propulsion, US Admiral Hyman G. Rickover, whose insistence on the highest standards of competence and accountability in all matters related to nuclear technology are legendary and persist to this day.

India’s original introduction to nuclear propulsion was through Russia, with which it was aligned in past times.

The Russian Navy has not achieved the high safety levels of Western navies and now that India is moving out of the Russian orbit by joining the Quad geostrategic grouping, it is not surprising that France is now taking the place once occupied by Russia, at least as far as nuclear propulsion is concerned.

For Australia, the opportunity is to join this movement in a manner that reflects the current relationship with France, the potential relationship with India through the Quad and the likely change of domestic attitudes towards nuclear power while recognising that we are at the low point of a learning curve where we can benefit from India’s experience with nuclear submarines even as a nuclear power in the full sense, and from France’s experience with foreign recipients of their submarine expertise for both conventional and nuclear propelled submarines.

In conclusion, this proposed roadmap should not cause concern regarding Australia’s continuing commitment to non-proliferation of nuclear weapons even though both proposed collaborators are nuclear weapons powers themselves.

The roadmap is about nuclear power for non-weapons use and is altogether different in nature to nuclear weapons technology.

Christopher Skinner served 30 years in the Australian Navy as a weapons and electrical engineer officer in six surface warships, including all three of the previous guided missile destroyers. He was seconded to the US Naval Sea Systems Command to manage the trials of the USS Oliver Hazard Perry FFG-7 first of class, and was the initial project director for the RAN Anzac Frigate Program. His interest in nuclear power for submarines is more recent and is reflected in his membership of the Engineers Australia, Sydney Division Nuclear Engineering Panel, the Australian Nuclear Association and the American Nuclear Society. He is also associated with several other organisations and institutes engaged in geopolitics, technology and submarine matters.

The views expressed above are entirely those of the author and are not endorsed by any of the organisations of which he is a member.

Login

Login