Australia isn’t alone in facing questions about the amount of firepower available to our surface fleet and recognising this, it appears that BAE Systems has been quietly working away on a next-generation destroyer concept building on the Type 26 base, with some impressive results.

As an island nation, Australia’s sovereignty, security, and prosperity is intrinsically linked to our maritime surrounds and the uncontested and unmolested access to the global maritime commons.

Driven in large part by the continued expansion of Beijing’s own already formidable naval forces, coupled with the rising capability of emerging powers throughout the Indo-Pacific, the relative power and capability of the Royal Australian Navy’s surface fleet has been called into question.

Front and centre for these concerns is the declining number of missile cells and accordingly firepower the Royal Australian Navy can bring to bear at any given time. This reality has drawn the attention of many strategic policy analysts, thought leaders, and policymakers as the nation grapples with how best to equip the Navy.

Detailing this truly terrifying state of naval firepower, former Chief of Navy, Vice Admiral (Ret’d) David Shackleton explains, “In 1995, the Royal Australian Navy possessed 368 missile cells on its major surface combatants. By 2020, that had reduced to 208, a 43 per cent reduction in firepower. It will take until 2045 for the Navy to get back up to its 1995 capacity. From 2050, it will plateau at 432, a net increase of 64 cells.”

Unpacking this further, this time focusing on the number of hulls at sea, VADM (Ret’d) Shackleton adds, “By 2006, when the RAN’s final Anzac frigate, HMAS Perth, was commissioned, the class had 64 cells, but the ESSMs they contained were to be used for self-defence. In the interim, two of six older Perry Class ships were decommissioned to provide funds to upgrade the remaining four, including adding eight VLS cells. That gave each ship 48 cells, and an improved capability with the longer-range SM-2. After modernisation, the Perry Class went from six ships to four, but the total number of cells went from 240 to 192.

“In 1995, the RAN operated three guided missile destroyers, six guided missile frigates and the first of eight smaller frigates, with 368 missile cells in all, the most it has ever possessed. By 2020, the combined effect of several force structure changes meant that across its fleet of eight Anzac Class and three Hobart Class surface combatants, the RAN could provide only 208 cells,” Shackleton adds.

Recognising this serious shortfall in the face of mounting challenges and adversary capabilities across the Indo-Pacific, the Albanese government’s Defence Strategic Review has moved to reshape the Royal Australian Navy into a flexible, future-proofed force capable of meeting the tactical and strategic operational requirements placed upon the service by the nation’s policymakers.

The Albanese government has sought to respond to these challenges by initiating a “short, sharp” review into the composition of the Royal Australian Navy’s surface fleet to deliver “An enhanced lethality surface combatant fleet, that complements a conventionally armed, nuclear-powered submarine fleet, is now essential, given our changed strategic circumstances.”

At the core of this is the government’s push towards a dispersed fleet of “Tier 1” and “Tier 2” vessels, through “Enhancing Navy’s capability in long-range strike (maritime and land), air defence, and anti-submarine warfare requires the acquisition of a contemporary optimal mix of Tier 1 and Tier 2 surface combatants, consistent with a strategy of a larger number of small surface vessels.”

Amid all of this conversation, a number of naval shipbuilders have pitched proposals to the Australian government to solve these challenges and better deliver combat firepower and expand the survivability of the Royal Australian Navy.

Welcome contestants

Both the Spanish government and Navantia Australia have long pitched an expanded acquisition of the already in service Hobart Class destroyer fleet with a range of delivery options, which would provide Navy with an additional 114 missile cells at sea. This was reinforced by Warren King, former head of Defence Materiel Organisation, who told The Australian, “The air warfare destroyers have proved to be an admirable platform, they are efficient, they’ve got a lot of punch and they are affordable. We know how capable they are and we’ve got a navy that knows how to use them.”

Meanwhile, BAE Systems Australia has been quietly working away pitching a truly formidable warship proposal in an effort to spare the $45 billion Hunter Class frigate program from seeing major cuts to the ship numbers, proposing a major restructuring of the Hunter Class program to deliver a fleet of heavily armed guided missile destroyers concurrently with the Hunter Class frigates.

As part of the proposal, BAE Systems Australia’s pitch to the government in February was to deliver the first three Hunter Class vessels, before switching to deliver its first new air warfare destroyer, this would then result in a drumbeat seeing “The company would then build, alternately every two years, another frigate and then another destroyer until nine ships in total were built — six frigates and three destroyers — although final numbers and configuration would be up to the government.”

Not to be outdone, BAE Systems UK has been busy working behind the scenes on a truly formidable surface combatant billed as the replacement for the Royal Navy’s Type 45 Daring Class guided missile destroyers, while leveraging the Type 26, Global Combat Ship hull form as a basis for this vessel, with some interesting ramifications for Australia’s own future shipbuilding endeavours.

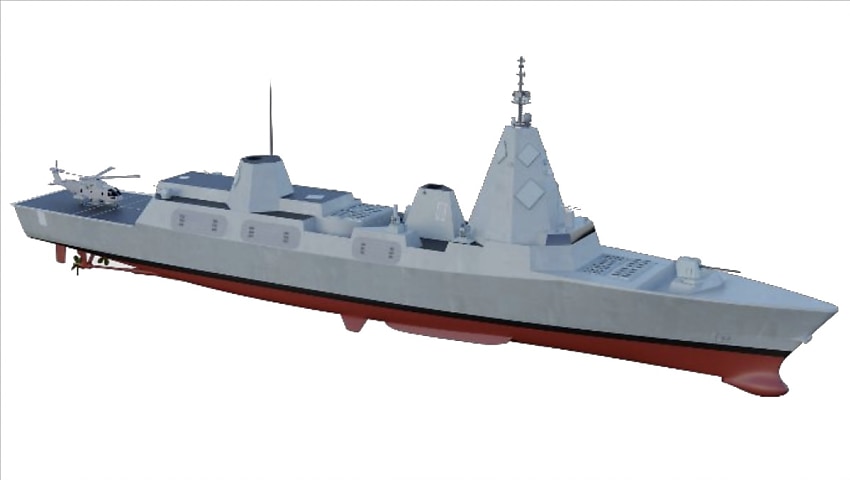

Presented as a piece of concept art in a BAE Systems presentation titled, “Fire Safety and Damage Control Warship Design - Now and into the future”, which focuses on the lessons learned through operations (including the HMAS Westralia fire) and the design process to mitigate the impact of fire damage, while maintaining water tight integrity in the face of combat operations through the applied use of automation.

Appearing on page 12 of the presentation, with an indicative time line for delivery commencing in the mid-2030s is the Type 83 destroyer concept, which reveals a significantly larger vessel than the planned Type 26/Hunter Class ships, respectively, with an incredibly formidable weapons load out.

Taking a closer look (zoomed in and cleaned up thanks to our amazing design team) we getter a better sense of the scale of this truly formidable warship currently being considered — this reveals an immense warship, of at least 12,000 tonnes in weight, bringing it close to the size Chinese Type 055 guided missile cruiser.

Additionally, the image shows an immense weapons payload, including the standard five-inch main gun, two Phalanx Close in Weapons Systems, two 30 or 40mm guns, and two additional unidentified close in weapons systems.

However, by far, the most significant payload is the missile payload, split into two banks of what appears to be Mk 41 vertical launch system cells, with an estimated capacity of 64 VLS per bank, bringing the total missile cells to 128 per ship.

Equally interesting is the apparent integration of Australia’s own CEAFAR 2 or a derivative radar system into the main mast and secondary mast, aft over the main hangar, raising interesting questions about the role the AUKUS agreement will play in shaping the development and delivery of a joint radar system, combat management system, and combat system interface.

It is important to understand, that while this is speculation based on an image in a PowerPoint presentation, the scale and scope of this future destroyer, coupled with Australia’s own future needs, presents an interesting path forward, worth consideration and collaboration under the auspice of the AUKUS trilateral agreement between Australia, the US, and the UK.

Additionally, while uncrewed surface and submarine vehicles will increasingly play a role in the composition of both the surface and submarine fleets respectively, crewed vessels will continue to play a central role in the way in which the nation enforces the concept of impactful projection.

Equally, the government has already recognised that the Australian Navy will need to grow in both mass and capability while also committing to the continuous naval shipbuilding capability in-country providing an opportunity for the government to not only ramp up the delivery of critical capability, but also provide much needed certainty to the industry.

BAE Systems Australia was contacted for comment but have not responded at the time of publication.