An updated report to Congress detailing the progress and planning of the US Navy’s next large surface combatant (LCS), the DDG(X), has revealed tentative plans for an expanded fleet of large surface combatants to help the US Navy meet its global responsibilities.

Hailing from relatively modest roots in terms of warship design and role, contemporary destroyers have evolved to become formidable surface combatants and the undisputed multipurpose first responders for major navies around the world.

Large hulls, long ranges, and high speeds support a wide variety of mission profiles, from convoy and battle-group escort for high-profile assets like aircraft carriers and amphibious warfare ships to maritime security, land attack, anti-air and anti-submarine defence, destroyers are the core of the navy.

These core roles have further evolved with the advent of increasingly powerful combat systems and advanced weapons systems including ship-mounted lasers and hypersonic missiles, driving the role evolution of destroyers to include things like ballistic missile defence (BMD), while enhancing the already formidable capabilities of these key platforms.

Throughout the Indo-Pacific, destroyers are rapidly being commissioned or transferred to the region to beef up navies and secure key strategic assets, lines of communication and support power projection platforms.

Largely by the growing capabilities of the People’s Liberation Army-Navy (PLA-N) following the introduction of increasingly capable Type 052C and Type 052D guided missile destroyers, culminating in the 13,000-tonne Type 055 destroyers which have prompted many across the Indo-Pacific to begin their own destroyer modernisation fleets.

Both Japan and South Korea have kickstarted plans for increasingly capable Aegis-based guided missile destroyers in the form of upgraded variants of the Sejong the Great Class destroyers in the case of South Korea and two, immense 20,000-tonne, “Aegis System Equipped Vessels” (ASEV) destroyers/cruisers.

Australia has announced plans to acquire Tomahawk cruise missiles, Naval Strike Missiles and a host of air-launched platforms, like the Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missiles (JASSM-ER) and Long Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM) as a means of beefing up its anti-surface capabilities, while BAE Australia, Navantia Australia, and a host of other companies have responded by presenting various evolutions of designs to expand the Royal Australian Navy’s lethality at sea.

Meanwhile, across the Pacific, the United States has begun fielding upgraded variants of the venerable Arleigh Burke Class destroyers, with a growing number of Flight II, Flight II/B variants at sea and planned to undergo a range of complex radar upgrades to enhance their combat capabilities.

The US destroyer fleet is further enhanced by the currently growing fleet of Flight III Arleigh Burke Class destroyers which are designed to fulfil the role provided by the retiring Ticonderoga Class cruisers; however, the United States Navy has recognised that Arleigh Burke hull form has reached its power generation and weapons payload capacity.

This level of design maturity and the resulting limitations on the existing hull forms, combined with the growing capabilities of the PLA-N’s own fleet of advanced destroyers has prompted the US Navy to begin detailed design work on their next generation of guided missile destroyer, or DDG(X).

Gathering pace, but ‘reduced’ LSC fleet

In light of the rapid expansion of Beijing’s own naval capabilities, coupled with renewed Russian naval capabilities in the Pacific and Atlantic and the ageing nature of much of the US Navy’s large surface combatant fleet, the United States has sought to accelerate the development and acquisition of the DDG(X) platform and, importantly, an expansion of the LSC fleet as a whole.

Highlighting this, the Congressional Research Service report details the current ambitions of the US Navy for the DDG(X) design, stating, “The Navy’s DDG(X) program envisages procuring a class of next-generation guided-missile destroyers (DDGs) to replace the Navy’s Ticonderoga (CG-47) Class Aegis cruisers and older Arleigh Burke (DDG-51) Class Aegis destroyers. The Navy wants to procure the first DDG(X) in FY2032. The Navy’s proposed FY2024 budget requests US$187.4 million (AU$276.9 million) in research and development funding for the program.”

Unpacking the long-term implications of this, the CRS states, “The Navy refers to its cruisers and destroyers collectively as large surface combatants (LSCs). The Navy’s current 355-ship force-level goal, released in December 2016, calls for achieving and maintaining a force of 104 LSCs. The Navy’s FY2023 30-year (FY2023–FY2052) shipbuilding plan, released on April 20, 2022, summarises Navy and OSD studies outlining potential successor Navy force-level goals that include 63 to 96 LSCs.”

Serving as a driving force behind this is the aforementioned age of both the Arleigh Burke Class and the Cold War-era Ticonderoga Class (CG-47) of guided missile cruisers, which the CRS details, stating, “The Navy procured 27 CG-47s between FY1978 and FY1988. The ships entered service between 1983 and 1994. The first five, which were built to an earlier technical standard, were judged by the Navy to be too expensive to modernise and were removed from service in 2004–2005. The Navy began retiring the remaining 22 ships in FY2022 and wants to retire all 22 by the end of FY2027.

“The first DDG-51 was procured in FY1985 and entered service in 1991. The version of the DDG-51 that the Navy is currently procuring is called the Flight III version. The Navy also has three Zumwalt (DDG-1000) Class destroyers that were procured in FY2007–FY2009 and are equipped with a combat system that is different than the Aegis system,” the CRS report further explains.

Shifting to the planned acquisition number for the proposed DDG(X), the CRS report highlights a planned procurement pace in accordance with “The Navy’s FY2024 30-year shipbuilding plan projects LSCs being procured in FY2032 and subsequent years in annual quantities of one to three ships per year.”

Cost has also emerged as a major concern for the US Navy as it faces the potential of multiple years of flat or declining budgets, with an expectation that the proposed DDG(X) could cost up to an astronomical US$3.4 billion per ship, potentially limiting the production run of the ships.

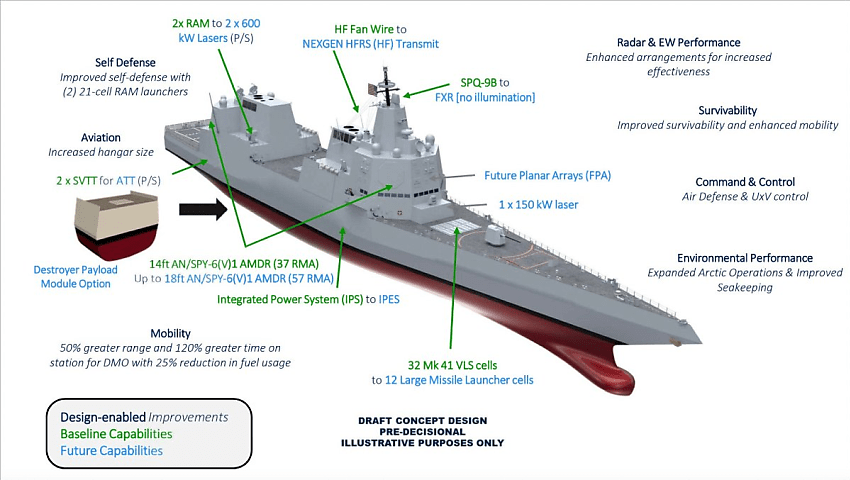

As a transformational platform for the US Navy, it has spared no expense in the design phase for the DDG (X) concept, with a host of ambitious standard design features, with a host of additional through-life upgrades and capability enhancements designed into the hull form from the earliest stages.

This is key to ensuring that the US Navy large surface combatant fleet can qualitatively overmatch any potential adversary.

Yet as transformational as the DDG(X) platform could prove to be, both the CRS and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) believe this would have major cost implications on an already constrained US Navy budget, with the CRS stating, “The October 2023 CBO report estimates the DDG(X)’s average procurement cost in constant FY2023 dollars at US$3.2 billion to US$3.5 billion – about 33 per cent to 40 per cent more than the Navy’s estimate (shown in the CBO report) of $2.4 billion to US$2.5 billion. The CBO and Navy estimates are about 45 per cent to 59 per cent, and 9 per cent to 14 per cent, respectively, more than the DDG-51’s procurement cost of about US$2.2 billion. The CBO report states that “the Navy’s estimates imply that the DDG(X) would cost about 14 per cent more than the DDG- 51 Flight III but would have a full-load displacement that is 40 per cent greater. Such an outcome, however, seems unlikely given the history of the Zumwalt Class DDG-1000 guided missile destroyer”.

Final thoughts

The growing realisation is that both the United States and allies like Australia will need to get the balance of its military and national capabilities just right, not just to support the US as part of a larger joint task force, but to ensure that the Australian Defence Force can continue to operate independently and complete its core mission reliably and responsively.

Critically, where much of the commentary around the AUKUS partnership has focused heavily on the design, development, and acquisition of a common nuclear submarine platform, enhancing capability aggregation, driving down costs and expanding the global impact of the alliance — in light of the potential costs associated with developing the DDG(X) Class, combined with transformation technology inclusions like hypersonic weapons provides potential opportunities for allied partnership under the auspice of AUKUS.

This is particularly timely for the partners, while the US has a well-established program, the UK Royal Navy is in the early stages of developing a concept for their Type 86 Destroyer replacement program to replace the Type 45 Daring Class destroyers and Australia’s Hobart Class destroyers are relatively young and slated to undergo an extensive modernisation program in the coming years, the timeline for delivery for the DDG(X) intersects perfectly with initial planning stages for the replacement of both the Hobart Class and the Type 45 fleet.

For Australia, this could provide immense opportunity across the shipbuilding enterprise, providing certainty for shipbuilders working on the Hunter Class frigates, enabling them to shift from the Hunter Class to the DDG(X) once the production run has ended.

Doing so would support economic development and also providing the United States with additional avenues for a distributed build to support greater acquisition through the sharing of a common design and the ensuing economies of scale.

This begs an important question: Is it time for Australia to make the request to join the DDG(X) program?

Get involved with the discussion and let us know your thoughts on Australia’s future role and position in the Indo-Pacific region and what you would like to see from Australia’s political leaders in terms of partisan and bipartisan agenda setting in the comments section below, or get in touch at