Following revelations that the US would begin retiring its fleet of Cold War-era B-1 Lancer bombers due to increased focus on the US Air Force’s next-generation B-21 Raider stealth bomber, could reviving the B-1R regional bomber concept provide Australia and other regional allies with a credible regional strike capability?

For Australia, the retirement of the F-111 platform, combined with the the limited availability of the Navy’s Collins Class submarines, has left the nation at a strategic and tactical disadvantage.

These factors have limited the nation’s capacity to successfully intercept and prosecute strikes against, air, land and sea targets that threatened the nation or its interest through the sea-air gap as identified by Paul Dibb during the 1986 Dibb Review and subsequent white papers, which have formed the backbone of Australia’s strategic doctrine.

While the acquisition of the Super Hornets in the mid-to-late 2000s and the acquisition of the fifth-generation F-35 Joint Strike Fighter to fulfil a niche, low-observable limited strike role have both served as a partial stop-gap for that lost capability, the nation has not successfully replaced the capability gap left by the F-111.

Australia’s unique geographic position and its surrounding area of responsibility means that long-range strike platforms, especially long-range air power have long served as a key component in the nation’s strategic and tactical calculations beginning with the heavy bomber force established throughout the Second World War.

However, the rapidly evolving period of peer and near-peer competitor contest, largely driven by the United States and China’s clash of ideas, has prompted many within Australia’s strategic policy and defence communities to lobby government to seriously invest in the long-range strike and strategic deterrence capabilities of the Australian Defence Force.

Enter Air Marshal (Ret’d) Leo Davies and his immediate predecessor, Air Marshal (Ret’d) Geoff Brown, speaking to Catherine McGregor in The Australian, who articulated the changing balance of power Australia finds itself neck-deep in:

“The force that we used to carry out nation-building in the Middle East cannot defend our sea lines of communication or prevent the lodgement of hostile power in the Indo-Pacific region.

“Everyone thought conventional wars were almost a thing of the past. That judgment now looks rather optimistic. We need to ensure that our air, space and naval assets can impose transaction costs on those who would infringe on our vital trading interests. That must entail investment in air power.”

Recognising this, combined with the revelations that the US Air Force is planning the retirement of its fleet of Boeing-designed B-1 Lancer bombers, originally designed as a stop-gap between the planned retirement of the B-52 Stratofortress and replacement with the original stealth bomber, the B-2 Spirit, is it worth reviving a concept from the early 2000s?

Originally designed to supplement the US bomber fleet to support combat operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, the proposed B-1R regional bomber variant would breathe new life into the US Air Force’s B-1 fleet and support its role within Global Strike Command – but how can it support the long-range strike needs for Australia and regional allies?

Shifting from a global focus to a regional focus

When originally proposed during the late 1960s, the B-1A was designed to conduct high-speed (Mach 2.2) deep penetrating strikes against heavily defended targets deep within Soviet territory – the evolution of the B-1 and the eventual introduction of the B-1B saw a number of design concessions provide the US Air Force with a potent strike capability.

Shifting changes in the global power dynamics and the need for a persistent, heavy strike capability eventually caused the US Air Force to begin the evaluation of several concepts to ensure that the US Air Force had a credible bomber capability beginning in the late 2010s – this gave rise to concepts like the FB-22, a strategic airlifter-based “arsenal plane” and the B-1R regional bomber.

Breaking these down, the US Air Force Magazine from 2008 broke down the options from across the US defence industry ecosystem:

- Northrop Grumman: The program manager for future strike systems, Charles Boccadoro, said the firm submitted eight concept proposals. These included a B-2 Global Strike Capabilities Initiative, a low-risk block upgrade to the highly successful stealth bomber. (The company did not propose restarting new B-2 production.) A higher risk, “cutting edge” option was an Unmanned Regional Attack aircraft derived from existing unmanned aerial vehicle programs. Finally, there was a “niche” option – a conventionally armed intercontinental ballistic missile. Boccadoro noted that a conventional ICBM could quickly destroy a hardened or buried target anywhere in the world. However, it could not maintain a persistent presence in the battlespace.

- Lockheed Martin: Kevin J. Renshaw, manager of advanced air combat programs, outlined four system proposals. These included: the FB-22, an “arsenal ship” aircraft based on the C-130 airframe, a hypersonic missile tipped with the so-called “Common Aero Vehicle”, and a “clean sheet bomber” built from scratch. The FB-22 and the arsenal ship are probably “easier to get to”, he said, but all of the concepts were deemed achievable by 2015. John Perrigo, another Lockheed manager, asserted that USAF might go for an unmanned system, even for the interim capability.

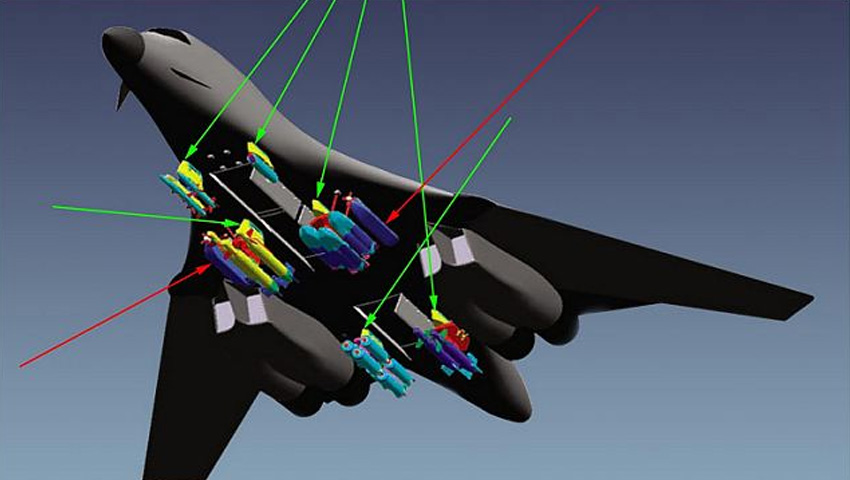

- Boeing: The director of global strike integration, Rich Parke, noted that his company had submitted six proposals. These included a Prompt Global Strike Missile using decommissioned ICBMs, an X-45D direct-attack unmanned combat air vehicle with increased range and payload, a blended wing body arsenal ship aircraft that could hold 96 cruise missiles, and a “B-1R” bomber. Parke said the B-1R (R stands for “regional”) would be a Lancer with advanced radars, air-to-air missiles, and F-22 engines. Its new top speed – Mach 2.2 – would be purchased at the price of a 20 percent reduction of the B-1B’s combat range.

This concept would see the US Air Force take delivery of an immensely capable strategic and tactical force multiplier, with minimal risk as a result of leveraging existing technologies, including the F-119 Pratt & Whitney engines, the precursor to the F-35’s F-135 engine, modern, off-the-shelf avionics and active electronically scanned array radar.

It was envisaged that the 20 per cent reduction in combat radius would give the proposed B-1R with a combat range of approximately 2,394 nautical miles or 4,433.6 kilometres, incorporating a series of air defence weapons systems to ensure that the upgraded platform was capable of defending itself and running should it need to.

Additionally, modifications to the existing external hardpoints would be modified to allow an increased overall loadout, on top of the standard payload of 57,000 kilograms, enabling tactical and strategic flexibility in a credible deterrence package.

US Air Force retirement and capability aggregation

Australia doesn’t require a first strike capability like the B-21 Raider, as the Australian Defence Force and its individual component branches are all designed to work both in a “joint”, multidomain environment while also supporting coalition forces, providing a credible path to introducing a replacement and upgrade to Australia’s retired F-111s.

Recent revelations in the US 2020 National Defense Authorization Act will see a number of major acquisitions, organisational restructures and modernisation programs to support America’s shift away from decades of conflict in Afghanistan and the Middle East towards the great power competition focus of the Indo-Pacific.

A key component of this is the USAF’s decision to bring forward the retirement of 17 of its oldest Cold War-era B-1 Lancer aircraft as the costs associated with keeping the platforms airborne and ready to support the mission of Global Strike Command becomes increasingly costly and time consuming – with a proposed retirement date for the full fleet of 66 airframes by 2036.

Australia’s need to re-establish a credible long-range strike capability necessitates a major rethink for the nation’s strategic policymakers, with the planned retirement of the B-1 platform an enticing opportunity to develop such a capability, which would enable the Royal Australian Air Force to establish and maintain a regionally superior strike capability.

Drawing on existing technologies also serves to de-risk the platform modernisation and acquisition costs of an Australian B-1R, while the existing airframes would further serve to lower the costs associated – from a capability aggregation standpoint, the platform would provide a known quantity for US and allied forces.

None of this is capable without increases to the ADF budget, which is highlighted by ASPI senior analyst Malcolm Davis, who explained the need for renewed focus on the budget allocation for Defence to Defence Connect at the Avalon Airshow earlier this year:

“The government aspiration of spending 2 per cent of GDP on defence is simply not enough any more. We need to look at planning our force structure, our capability requirements and spending on a number of factors, including allied strengths and potential adversarial capabilities, not arbitrary figures.

“It is time for us to throw open the debate about our force structure. It is time to ask what more do we need to do and what do we need to be capable of doing.”