A Defence scientist has revealed how he’s using a Star Trek-style game to research how the Australian Defence Force can respond to a cyber attack.

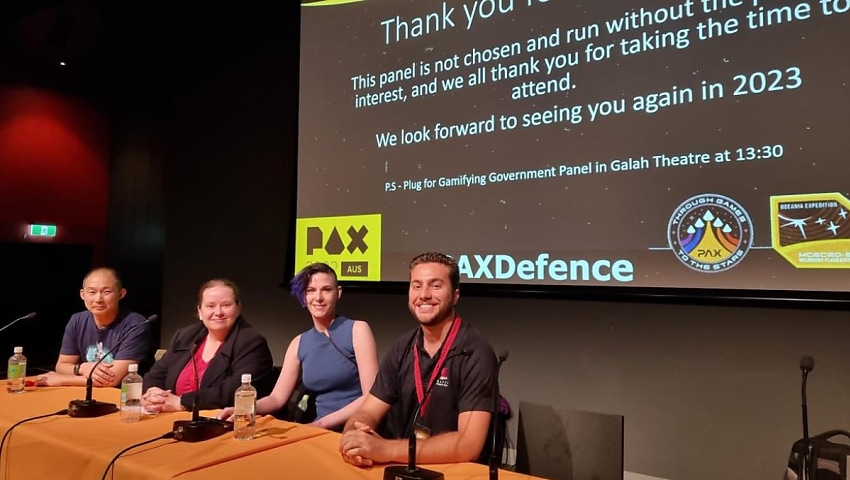

Alex Rohl told a gaming convention how he uses the player data captured by Artemis: Spaceship Bridge Simulator to simulate combat management systems.

“Our research is being applied to dynamic enterprise systems, as well as static bespoke systems, in a military context,” he said.

Artemis places you on a Star Trek-like bridge where players have to communicate between roles such as captain, communication, weapon control, engineering and more.

“Under the hood, networked games share enough similarities to real systems to enable fundamental research at the unclassified level, while also allowing universities, students and industry to participate in the work,” said Rohl.

Calling games “the perfect testbed” for research collaboration on simulators, Rohl suggested that “Perhaps, in the future, Defence might sponsor the creation of video games as a platform for further research collaboration.”

Rohl’s role as a data science researcher sees him support Defence to “withstand, recover from and adapt to compromises of its military systems that use, or are enabled by, cyber resources”.

There is a history of gaming influencing training in defence, including in the ADF.

As Robert Carpenter and Cliff White of the Defence Department unveil, evidence of Australian soldiers benefiting from gaming dates back to the early 1980s, where the strongest participants of a gunnery training course to fire the Leopard 1 main battle tank had been practicing skills on an arcade game in the soldier’s club.

“In this case, the soldiers were learning the concepts of leading a target, observing the fall of shot, and changing their aim. This basic education enabled them to learn quicker during the subsequent training,” the document said.

This, however, was never funded by the government.

As Dr Susannah Whitney discusses, not just any game is set to be a beneficial training tool. Her work focuses on serious games, which are the kind that are built and used purely for training and teaching purposes, rather than entertainment.

Dr Whitney said that while the use of gaming in military training has been met with an enthusiastic response, particularly with younger generations, they did not always prove to be ideal training tools.

“Games and games technologies may have training potential but it’s important that decisions about the use of games and gaming technology are informed by evidence,” Dr Whitney said.

“We need to understand if the technology works, and how best it can be employed.”

The use of video games-based technologies in military training, research, simulation and innovation is currently being researched by defence scientists. Investment in this research bolsters the Australian footprint in the cyber and technology industries.