Should Australia’s new prime minister begin his term in office by promoting Japanese membership in AUKUS?

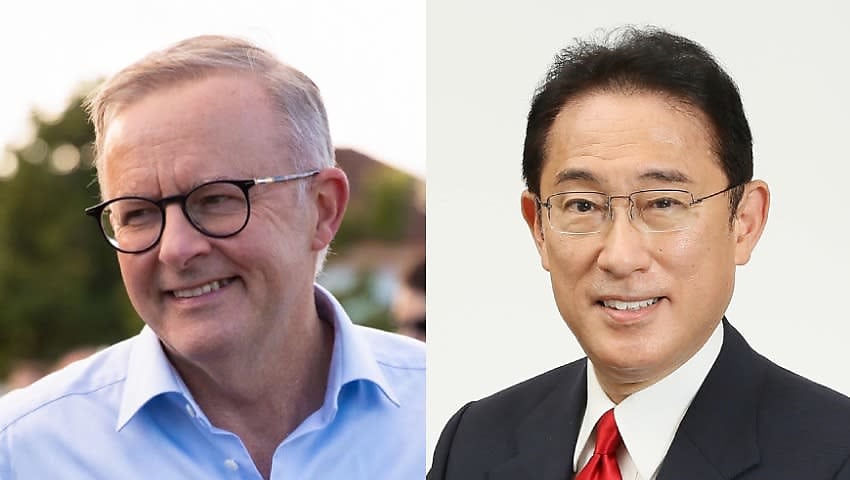

Australia’s 31st prime minister, Anthony Albanese, has been swiftly sworn into office ahead of an in-person Quad leaders’ meeting in Tokyo, Japan on Tuesday (24 May).

Prime Minister Albanese will be thrown straight into the deep-end, meeting with US President Joe Biden, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida to discuss the Quad’s strategic agenda in the Indo-Pacific amid shared concerns over China’s continued aggression.

So, what could Prime Minister Albanese bring to the table?

The new PM has said a “three pillar” strategy would shape the Albanese government’s foreign policy agenda, focused on:

- Australia’s alliance with the United States;

- Deepening regional relationships; and

- Support for multilateral forums.

This is expected to include promoting greater action on climate change in hopes a renewed multilateral response would help build trust among regional partners.

“One of the ways that we increase our standing in the region, and in particular in the Pacific is by taking climate change seriously, and the Biden administration and Australia, I think, will have a strengthened relationship in our common view about climate change and the opportunity that it represents,” he said in an address to the National press Club ahead of the federal election.

But how else could Prime Minister Albanese advance his three-pillar strategy at his first Quad leader’s meeting?

According to Mercedes Page – fellow, International Strategy Forum at the Schmidt Futures and a former Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade official – Canberra and Washington could use the Quad meeting to discuss opportunities for Japanese membership in AUKUS or “JAUKUS”.

“There’s been persistent speculation that Japan will join AUKUS since it was announced in September last year,” she writes in ASPI’s The Strategist.

“Japan has made a number of positive statements about the trilateral technology-sharing partnership.”

Page cites remarks from Japan’s ambassador to Australia, Shingo Yamagami, who said last November: ‘We have been told there are some instances or areas where AUKUS members may need Japanese cooperation and participation and we are more than willing to do our contribution.’

Japanese support for AUKUS could come “sooner rather than later”, Page continues, given the AUKUS partners’ recent commitment to collaborate on hypersonics, counter-hypersonics, and electronic warfare capability.

“With Japan’s expertise and capabilities in these areas, it wasn’t surprising when a report appeared in Japanese newspaper the Sankei Shimbun a few days later alleging that AUKUS members had each informally reached out to their Japanese counterparts to sound out opportunities for Japan to join the partnership,” she writes.

“The report was quickly shot down by Tokyo and Washington, with the White House declaring the focus was on finalising a trilateral program of work.

“That may be so (for now), but it still makes a lot of strategic sense to make ‘JAUKUS’ happen.”

Page goes on to note Japan’s shared security concerns and its “proactive” defence of the rules-based order.

“Facing the realities of an increasingly unstable region, Japan is updating its security policy settings at its highest levels,” she continues.

“It is working on updating its national security strategy for the first time since 2013 alongside a raft of other defence and security policies that are due for release later this year.”

According to Page, JAUKUS would just build on existing bilateral security ties between Tokyo, Canberra, London, and Washington.

Japan and the United Kingdom are currently in negotiations to sign a reciprocal access agreement, similar to the deal struck with Australia in January, while the US remains key to Japan’s defence and security posture.

“These arrangements position Japan and AUKUS members on the same page and structural levels, meaning it wouldn’t be a big jump to take the relationship to the JAUKUS level,” Page adds.

Moreover, JAUKUS would leverage Japan’s vast experience in the advanced technology space.

“[AUKUS] is clearly not just about submarines, and Japan would benefit from enhanced access to broader expertise and technology from Australia, the UK and the US,” Page notes.

“With Japan in North Asia, facing China on one side and Russia (which it’s still technically at war with) above, a Japan with access to all that AUKUS can offer is in all our interests.”

Further, Page argues opening AUKUS to Japan would also dispel Chinese propaganda, which has described the deal as “Anglosphere”.

“It might also go some way to reassuring Southeast Asian nations and other countries in the region that are still inclined to look warily at AUKUS,” she writes.

“Japan has a well-deserved reputation for being a positive and constructive partner in the region, with a history of engagement, balancing and deterrence in its relationship with China.

“It would also help counter ongoing Chinese disinformation regarding AUKUS and nuclear proliferation if Japan, the only country to suffer a nuclear attack, finds the claims baseless.”

Page concludes: “With Japan more than willing to step up to the plate, as two out of the three AUKUS leaders meet in Tokyo next week for the Quad, let’s hope there’s some momentum on the sidelines to also make JAUKUS happen.”

Get involved with the discussion and let us know your thoughts on Australia’s future role and position in the Indo-Pacific region and what you would like to see from Australia's political leaders in terms of partisan and bipartisan agenda setting in the comments section below, or get in touch with