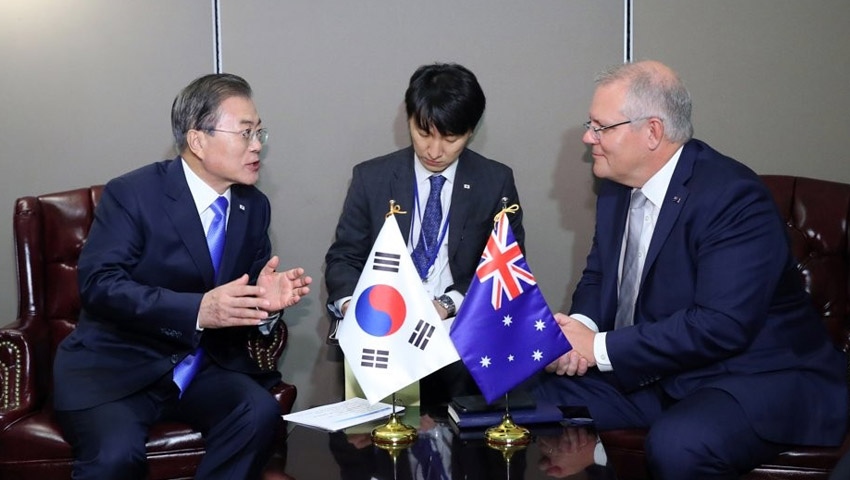

Prime Minister Scott Morrison and his South Korean counterpart, President Moon Jae-in, have outlined plans for an expanded period of collaboration on key national security issues, including defence, industry development and energy security, during a meeting at the UN Headquarters in New York.

Alliances are pivotal in maintaining prolonged periods of peace and prosperity – Australia’s position in the Indo-Pacific has been contingent on the alliance with the US. However, as the region continues to evolve, Australia’s core economic and strategic relationships also need to evolve.

Since 2009, successive Australian governments have sought to slowly shift the nation’s focus away from the Middle East towards what has become known as the Indo-Pacific. The most recent Foreign Policy White Paper, released in 2017, has formally identified the shift in the global power paradigm and its impact on Australia’s long-term economic, political and strategic interests in the 21st century.

Australia emerged from the Second World War as a middle power, essential to maintaining the post-war economic, political and strategic power paradigm established and led by the US. This relationship, established as a result of the direct threat to Australia, replaced Australia’s strategic relationship of dependence on the British Empire and continues to serve as the basis of the nation’s strategic policy direction and planning.

This international rules-based order has played a critical role in supporting Australia’s long-term development and is anchored by economic and strategic alliance frameworks. However, the rise of totalitarian nations, including China, Russia and the like, are challenging the order, which is recognised by the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper, which states:

“The international order is also being contested in other ways. Some states have increased their use of ‘measures short of war’ to pursue political and security objectives. Such measures include the use of non-state actors and other proxies, covert and paramilitary operations, economic coercion, cyber attacks, misinformation and media manipulation.

“International rules designed to help maintain peace and minimise the use of coercion are also being challenged. Australia’s security is maintained primarily through our own strength, our alliance with the United States and our partnerships with other countries. Australia’s security and prosperity would nonetheless suffer in a world governed by power alone. It is strongly in Australia’s interests to seek to prevent the erosion of hard-won international rules and agreed norms of behaviour that promote global security.”

Recognising these factors, regional powers like Australia, Japan and increasingly South Korea have sought to maximise the integration of their economies, militaries and political decision-makers in order to combat challenges ranging from energy security, freedom of navigation, climate change, rogue states, cyber threats and traditional great power rivalries.

Strengthening the economic and strategic bond

Korea is Australia’s fourth-largest trading partner and a growing source of foreign investment. This was further reinforced in December 2014 with the entry into force of a free trade agreement (Korea-Australia Free Trade Agreement or KAFTA) between the two countries – with the strategic partnership between the two nations dating back to Australia’s participation in the United Nations-led force during the Korean War.

As a nation within a similar story of economic and strategic development to that of Australia – that is, one firmly dependent on the global rules-based order established after the Second World War and led by the United States, in light of the continuing development of the Indo-Pacific and the shared challenges and opportunities, both nations have sought to further enhance their collaboration in key areas.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison and South Korean President Moon Jae-in have used the UN General Assembly Session held in New York to outline plans for a reinvigorated period of collaboration across a range of key issues, namely: trade, investment, infrastructure, industry, defence and arms development and a renewed focus on an expanded cooperation in the renewable energy sector, including the use of hydrogen.

This relationship is set to be further developed as a result of Korea’s growing participation in the development of Australia’s sovereign defence industry capability, with the Korean industrial behemoth recently down-selected as a contender for the multibillion LAND 400 Phase 3 program to replace the Army’s Vietnam-era M113 armoured personnel carriers and the LAND 8112 Protected Mobile Fire, self-propelled gun program.

Another area of particular interest between the two nations is the growing focus on energy security and the national security implications of energy availability, sustainability and climate change, with both nations engaging in high-level discussions about the development of hydrogen technologies amongst others.

Australian Minister for Resources and Northern Australia Matt Canavan has been in South Korea recently to sign a Letter of Intent to collaborate and develop a Hydrogen Action Plan.

Minister Canavan has been in the Republic of Korea for the last two days meeting with Korea’s Minister for Trade, Industry and Energy and a number of important industry groups and businesses including the Korea-Australia Business Council, the Hyundai Motor Company, the Korea Gas Corp. and Korea Resources Corp.

He has used his trade mission to release Geoscience Australia’s report for the National Hydrogen Strategy, Prospective hydrogen production regions of Australia, which identifies the regions in Australia that have a high potential for hydrogen production.

“I’ll explain how Australia has been investing heavily in hydrogen projects and outline our National Hydrogen Strategy, which will map out the steps we can take to develop a sustainable and commercial hydrogen industry. We have the resources, know-how, infrastructure and research base to produce and supply clean hydrogen to the world, and this report shows every Australian state and territory has regions with excellent prospects for hydrogen production,” Minister Canavan explained.

South Korea’s strategic situation could soon be Australia’s

Since the end of the Korean conflict, the two Koreas have maintained an often tenuous peace – defined by the promise of mutually assured destruction should hostilities bubble over.

While the US, Russia and China have sought to maintain the armistice for fear of conflict between the superpowers, the increasingly unpredictable North Korean regime combined with the competing economic, political and strategic interests driven by China has served to prompt a major strategic rethink in South Korea.

South Korea’s response has been driven by two distinctly different factors, namely, North Korea’s continued pursuit of reliable nuclear delivery systems and the conventional manpower and firepower of the North Korean Army; and rising power projection capabilities and willingness of China to assert its influence over a number of contested territories and sensitive sea lines of communication in the the South and East China Seas.

In response, Korea has embarked on a series of acquisition and modernisation programs targeting each of the branches of the Republic of Korea Armed Forces, playing a critical role in the nation’s response to its increasingly challenging geopolitical environment.

This includes a rapid expansion in the capabilities of the Republic of Korea Armed Forces, including the acquisition of new arsenal ships and Aegis powered guided missile destroyers, expansions to the Dokdo class amphibious warfare ships to serve as small aircraft carriers, a fleet of powerful new conventional attack submarines and the introduction of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter as the nation transitions to a fifth-generation force.

Korea’s focus on establishing itself as a regional power capable of intervening in regional affairs serves as a model for Australian force structure planners – the comparable economic, political and demographic size of Australia and South Korea combined with the similarity in the platforms and systems operated by both nations serve as a building block for both interoperability and similar force structure models.

As an island nation, Australia is defined by its relationship with the ocean. Maritime power projection and sea control play a pivotal role in securing Australia’s economic and strategic security as a result of the intrinsic connection between the nation and Indo-Pacific Asia’s strategic sea lines of communication in the 21st century.

Opportunities for Australia

Australia can take advantage of the simmering relationships between the emerging regional powers – building on the nation’s longstanding economic, political and strategic relationships with nations like South Korea, Indonesia, Vietnam, Korea, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand and India, which all serve as powerful political, economic and strategic partnerships to expand and nurture.

While the economic potential of these nations – with a combined market of approximately 1.8 billion people eager to enjoy a western standard of living – serve as attractive and lucrative markets for expanding Australia’s own economic development and thus should not be ignored, these economic interests are, like Australia’s, dependent upon the enduring peace and stability of the Indo-Pacific.

Recognising this unifying factor, Australia can and should serve as the political and strategic glue as part of a broader alliance network, using the growing economies and organisations like the Mexico, Indonesia, the Republic of Korea, Turkey, Australia (MIKTA) multilateral organisation to separate from traditional alliance frameworks between Australia, the US and Japan – doing so empowers Australia to actively pursue its own regional interests in support of the broader rules-based order without being beholden to external alliance frameworks.

Your thoughts

The nation is defined by its relationship with the region, with access to the growing economies and to strategic sea lines of communication supporting over 90 per cent of global trade, a result of the cost-effective and reliable nature of sea transport. Indo-Pacific Asia is at the epicentre of the global maritime trade, with about US$5 trillion worth of trade flowing through the South China Sea and the strategic waterways and choke points of south-east Asia annually.

For Australia, a nation defined by this relationship with traditionally larger yet economically weaker regional neighbours, the growing economic prosperity of the region and corresponding arms build-up, combined with ancient and more recent enmities, competing geopolitical, economic and strategic interests, places the nation at the centre of the 21st century’s “great game”.

Enhancing Australia’s capacity to act as an independent power, incorporating great power-style strategic economic, diplomatic and military capability serves not only as a powerful symbol of Australia’s sovereignty and evolving responsibilities in supporting and enhancing the security and prosperity of Indo-Pacific Asia. Shifting the public discussion away from the default Australian position of “it is all a little too difficult, so let’s not bother” will yield unprecedented economic, diplomatic, political and strategic opportunities for the nation.

Get involved with the discussion and let us know your thoughts on Australia's future role and position in the Indo-Pacific and what you would like to see from Australia's political leaders in terms of shaking up the nation's approach to our regional partners, and the avenues Australia should pursue to support long-term economic growth and development in support of national security in the comments section below, or get in touch with